Jesus Carranco has an old battered wallet with a very valuable item in it: his green card. He’s been a permanent resident since 1988, the final year of U.S. amnesty for farm workers. The card is in pristine condition, preserved inside a special envelope. But he won’t be needing it anymore, because he just became a U.S. citizen. He passed his naturalization interview and test in June and made it official at a swearing-in ceremony last week.

“My first goal was to learn English, and then something changed in me and I said, no. I’m going to become a citizen first,” says Carranco, a matter-of-fact 61-year-old farm worker whose deeply tanned forearms bespeak decades behind the wheel of a tractor and in the field, planting, irrigating and harvesting vegetables. Carranco had surgery to repair his left knee last November, and he walks with a pronounced limp.

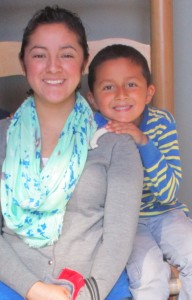

Jesus Carranco at Puente in the week after he earned his U.S. citizenship.

If you want to know what Mexican immigrants are capable of, consider that Carranco, whose schooling ended when he dropped out of the fifth grade, not only took the initiative to apply for citizenship through Puente, but studied for the test entirely on his own – memorizing 100 questions and answers with remarkable acuity.

“All day long I would be reading these questions to myself, four or five times a day,” he says. “I would lay in bed in the middle of the night and think about the questions.

I would wake up, make breakfast and have the questions with me while I cooked.”

Then there’s Gabriela (‘Gaby’) Flores, a 23-year-old student whose sister has Down Syndrome. Flores, who has been a green card holder for five years, decided that being a citizen would help her take care of her sister once she turns 18, through a family conservatorship. “She’s going to need someone to be her guardian, and my mom and my dad can do it now – but what happens after that?” she says.

Like Carranco, Flores turned to Puente to help her obtain, fill out and file her citizenship papers. At Puente, she learned that she qualified for a fee waiver – it normally costs $680 to apply for citizenship. But she paid nothing, and Puente filed her papers for free. She easily passed her written and naturalization tests, and made her official debut as a newly-minted citizen in May.

What’s the most thrilling part of being an American so far? “I’m very excited for jury duty. I can’t wait for that phone call,” she giggles.

Flores also finds herself paying closer attention to local and national politics now. She watches the news at night. “This time I know my vote counts to elect the next President,” she says.

At a time when some choose to cast aspersions on an entire class of immigrants from Mexico, Carranco and Flores represent the best kind of new American. For six years, Puente has provided immigration services to the South Coast community free of charge. It has processed 21 applications for citizenship. Most applicants also need help to prepare them for the naturalization test, so Puente connects them with members of the community who tutor them free of charge – sometimes for up to a year. Tutor and student inevitably become close and even end up going to the swearing-in ceremony together.

“The reason Puente started doing legal services is we had a family who was going to be deported, and by the father becoming a citizen, the family was able to file for Adjustment of Status here,” says Rita Mancera, Deputy Executive Director of Puente.

Thanks to support from the Grove Foundation over the years, Puente has helped people of all ages make the citizenship transition – from 18-year-olds to participants in their 70s. Mancera, who herself became a U.S. citizen three years ago, tries to get green card holders to apply for citizenship rather than pay $450 to renew every 10 years. Holding a green card limits the number of days one can spend outside the U.S., among other restrictions. She’s also been known to persuade young people with green cards to apply as soon as they turn 18 because Puente makes it so easy for them.

“If we weren’t here to help them with the process, they would have to find an attorney to represent them,” she says. “Often the perceived costs deter potential citizens from moving forward.”

Now Puente’s immigration services extend vastly beyond citizenship services. On June 3, Puente obtained Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) agency recognition, and Mancera received legal worker accreditation to assist participants with the immigration legal process. Puente plans to file accreditation for several other Puente staff members, which entails more than 40 hours of workshop training they completed early this year.

In the past, Puente would have an outside attorney review participants’ green card, visa and citizenship applications. The same went for applications under DACA, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. But now Puente can work autonomously.

“We are allowed to assist community members with their immigration issues without relying solely on attorneys,” explains Mancera. “The one exception is we are not allowed to go to court and present participants’ cases there. That said, we will continue to rely on the pro bono attorneys that assist Puente with our immigration-related work.”

Puente’s new status will be an enormous boon to the dozens of adults expected to apply for deferred deportation status and work permits under DAPA – provided the federal program survives its current legal challenge.

“It’s a tremendous asset for the community,” says Jack Holmgren, California Legalization Director of the Catholic Legal Immigration Network. Holmgren first approached Puente about pursuing BIA recognition, and helped guide staff members through the training and accreditation process his nonprofit provides.

“The South Coast is an out-of-the way place, and that geographic separation means people don’t get the services they need from trusted providers,” he adds. “Now Puente will be the trusted provider in the heart of the community for all their immigration needs.”

Puente’s BIA training was made possible through a generous grant from the San Francisco Foundation. Subsequent training is being supported by a grant from the Grove Foundation.

People have different reasons for wanting to be a U.S. citizen: some ideological, some practical. Carranco will retire soon, and hopes to spend more time in Mexico with the wife and children he misses so much. Some of them have petitioned the U.S. government for a green card, and have waited years for an answer; perhaps their father’s new citizenship status will speed things up.

“I like that feeling that I could help my family,” he says.