In his 35 years living and working in the fields of Pescadero, Jose Guadalupe Rogel Mendez has thought little of himself. Most of every day — from the moment he wakes before dawn in his bunk bed and heads to work on the ranch — is lived quietly thinking of his absent family, the wife and children who benefit from his labor.

Mendez is 72. And every day, he follows men half his age into the fields — planting peas, picking onions, bending stooping, pulling, lifting.

“I’m in search of an an ideal life. And thanks to God I have found what I’m looking for,” says Mendez, a tall, stoic man with a strong voice.

That ideal life involves spending half of each year in Villa Guerrero, Mexico, with his wife and nine children, before returning to Pescadero to work for Marchi Farms. (He has a green card.) By U.S. standards, his farm worker’s salary places him very close to the bottom of the totem pole. But in Mexico, Mendez has been able to build houses for seven out of his nine children. He also built a home for his wife, which includes some land to plant on. He continues to support his children when they need it, even though the youngest one is 24.

Thirty-five years ago, Mendez came to the U.S. looking for work, and Pescadero was the first place he stopped. “They treat me well here. I still don’t find the job difficult even though I have a lot of years on me,” he says.

When he’s in Pescadero, Mendez leads a life of quiet routine and asceticism. He doesn’t have a cell phone, a car, or a post office box (he shares with a friend). He never learned English. He sleeps on a lower bunk in a barracks owned by his employer, and shares a kitchen and bathroom with four other men (sometimes the number of roommates increases when the harvest season peaks). He works from sunup to sundown six days a week, and sometimes on Sundays too when there’s work for him.

He doesn’t cook the foods he likes, because food is expensive and he wants to send home as much money as possible.

“I just keep what’s needed for my lunch, dinner and clothes. Rent is not much. They only charge me $40 per month,” says Mendez. “I only get to eat meat once a week, but I try not to eat it at all. Meat is more expensive than vegetables and beans, and it’s also a diet that has helped me stay healthy.”

Mendez is not particularly sociable. He doesn’t join the other men at La Sala, Puente’s weekly program for migrant workers who eat, talk and play music together. He prefers to head to the beach and go fishing alone. He does not enjoy traveling, and in 35 years, he has never been farther afield than Watsonville.

“I’ve kept to myself mostly. I have some friends, but I don’t like sharing a lot about my life with everyone,” he says with a smile.

Considering his lifestyle, it wasn’t a huge surprise when Mendez walked into Puente looking for help in March, and was mistaken for someone who had recently moved to the area. In fact, when he mentioned health care, staff members mistakenly put him on the schedule as needing ACE, low-income residents, including undocumented individuals, who do not qualify for Medi-Cal and Medicare programs.

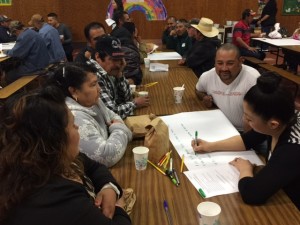

Puente’s safety net team consists of Corina and Laura Rodriguez. Mendez sat down with Corina Rodriguez, a community resource navigator who connects participants with Puente’s safety net services.

“I told him about ACE and he corrected me,” she recalls. “He said he was a permanent resident, and had been for 10 years. I said, ‘Oh, so you want Medi-Cal.’”

Mendez shrugged. He’d never even heard of Medi-Cal, which made no sense to Rodriguez.

“I told him, ‘If you’ve been here for such a long time, you must have had insurance all this time. How could you not have had insurance?’ We checked it in the county system, and sure enough, they had no record of him.”

He was like a ghost. Except for one important fact: Mendez did have Social Security, which meant he was also entitled to Medicare. Rodriguez helped Mendez apply for both Medi-Cal and Medicare right on the spot, even going so far as to make personal calls to the relevant agencies.

She was astonished that this affable 72-year-old man had managed to survive without taking advantage of so many services he was entitled to.

“He was so happy at the end that he pulled out his wallet and said, ‘Can I give you some money?’ I said, ‘no! It’s free.’ He said, ‘Well, can I get you something? Do you need anything?’” She laughs.

“He said that, in the past when he has gone out to look for help, he has never received anything near like what he had here.”

It’s not that Mendez is too proud to ask for help. In fact, he had been to Puente a handful of times — once to ask for help filling out a work document, another time to file his taxes with Puente’s free community tax program. It was during that tax session, in 2014, that Mendez learned he would be penalized if he could not prove he had medical insurance by April 2015.

“I asked a coworker of mine what I had to do to get insurance, and he told me I could come to Puente,” says Mendez. “I didn’t know what I was coming here to ask for.”

Remarkably, Mendez has been healthy all his life. The one time he saw a doctor, he learned first-hand just how expensive it is to be uninsured. “I had a checkup in the hospital in San Mateo. I felt dizzy. They ran some tests and charged me $2,200 for one day. They never did tell me what was wrong with me, but it went away,” he recalls.

Puente has enrolled 51 participants in health insurance since January 2015.

“I feel happy and joyous about it, because now I have what I need if I ever were to get sick,” says Mendez. Which is a relief, considering he’s 72.

Mendez is thinking about retiring soon. Next year could be his final planting season, after which he would return to Mexico for good. It’s time he enjoyed the fruits of his labor.

“I think that the most important thing is to feel as though you are able to help someone. Puente helped me and I would like to be able to help people more. I haven’t been able to help many people here, but I have been able to help a lot of people in Mexico.”

Please help Puente reach more community members like Mr. Mendez.

Make a gift today to our Silicon Valley Gives campaign and your contribution will be doubled!