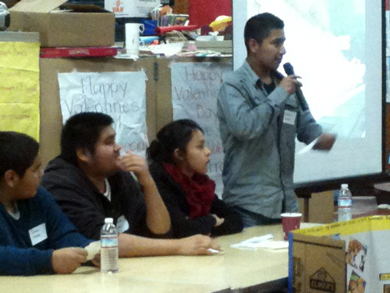

Pescadero High School students present their ideas for a town mural at at meeting of the Pescadero Municipal Advisory Committee (PMAC)

Valentin Lopez is 16. Some of his friends drink or use drugs, but he doesn’t. He’s seen what happens to people when they get hooked. One close family member has been using for years, and it troubles Lopez a lot.

“He drinks, he smokes, he uses drugs,” said Lopez. “My dad says, ‘You see what this is taking your family to.’”

Lopez, a student at Pescadero High School, joined an alcohol and drug prevention youth group this year, principally to fight what he sees as a growing trend toward troubling behavior among kids his age and younger. He’s been where they gather to drink and do drugs, the space under a bridge in town that’s covered in swear words and gang graffiti.

“Kids feel alone so they try to distract themselves,” he explained.

Puente founded several new alcohol and drug prevention youth groups in 2009 in addition to school based youth groups in 2011 to help students in the La Honda-Pescadero Unified School District (LHPUSD) talk about and cope with issues surrounding illegal substance use. Trained clinicians conduct the group meetings with students aged 10 to 18, using curriculum geared toward prevention and early intervention. The program was developed by Project Success and made possible by a grant from San Mateo County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services (BHRS), and is made possible because of a strong community partnership with LHPUSD, which has had a long history of providing drug and alcohol programming to its students.

Pescadero and La Honda are small towns – small enough to know what kids are doing. But Jorge Guzman, Director of Prevention Services, says people don’t understand how serious the problem has become. Guzman, 27, grew up in Pescadero and describes how much things have changed since he graduated from Pescadero High.

“Back then, high school meant marijuana. It meant some people doing meth and drinking,” he said. “Now it’s weed, meth, cocaine, pill popping, alcohol – and heroin for some.”

More than 60 percent of 9th grade students in the La Honda-Pescadero School District say it has become “very easy” to find alcohol and marijuana, according to their responses to the 2009-2010 California Healthy Kids Survey. Thirty-nine percent acknowledged getting drunk or high on school property at least once.

How could so many drugs be circulating in such a small community? And where are the parents? Guzman says most of the drugs come in from towns like Watsonville, and the absence of any dedicated police presence means there’s little deterrent to drug dealing. Some parents condone what they see as ‘typical’ youth experimentation with pot or ecstasy. Others will allow their kids to drink at home, because they figure at least they know where they are.

That reasoning is both false and dangerous, contends Guzman.

“It’s not okay. It’s not something that can continue to happen if you want to see kids go out there and do things for themselves… People have become accustomed to accepting it as a part of the culture,” he added.

The prospect of changing that culture is what motivates Guzman. He believes the real problem is that kids feel trapped in rural Pescadero. With support from a BHRS community partnership grant, a group of youth, including Lopez, recently started designing a town mural that depicts hope and resilience with the image of two palms cupped together releasing a flock of doves. The mural will read: “We dream with strength and courage and we succeed together.” The teens hope it will send a message to everyone about new beginnings.

“We’re trying to make this mural to ‘restart’ Pescadero – to make the bad image into a good image,” Lopez said.

For more information, contact Jorge Guzman at jguzman@mypuente.org— or 650.879.1691 ext. 142.