There’s a saying in Spanish: “Saber es poder,” which translates to “Knowledge is power.” Iris Fernandez witnessed the truth of those words when she brought 23 parents to the Half Moon Bay Library last month to reinforce a message about the importance of reading to their children at an early age.

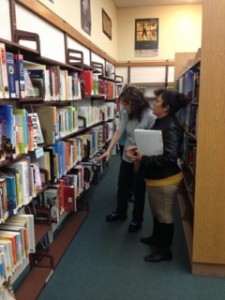

More than half the parents were visiting the library for the first time. Fernandez says the field trip, offered by Puente as part of its ongoing Abriendo Puertas (Opening Doors) workshop series, opened their eyes to the vast amounts of useful material that could be had for free. “There are magazines, books, tapes on how to learn English. They’re going to be offering book tablets, too. They were just thrilled,” she says. “We were trying to get everyone back to the bus, and we had to wait for them because they were checking out books,” she adds with a laugh. Thirteen parents signed up for new library cards on the spot.

Participants in Abriendo Puertas select books at the Half Moon Bay Library.

Puente staff didn’t know what to expect on March 2 when they launched Abriendo Puertas, a ten-part curriculum that teaches parents how to support their children’s growth and education with a focus on children aged 0-5. Would all 25 parents, many of whom work at least two jobs to keep their families afloat, be able to stick with the demanding program for 10 weeks?

They have. And they have been learning from each other, not just the curriculum, says Arlae Alston, Early Literacy Coordinator for Puente. Local parents themselves lead most of the sessions, as well as other community leaders and mental health and nutrition experts who were specially trained to present the material. The workshops are written in Spanish and specifically developed for Latino parents of small children. It’s not about perfect parenting, just about becoming more involved and engaged – even when parents are busy or stressed.

“This curriculum doesn’t ask parents to do anything that’s out of reach. We get their economic situations,” says Alston. “It’s not a guilt trip. We want them to feel successful.”

The program lasts from 6-8 p.m. on Monday nights, during which Puente provides childcare and dinner.

The material is interactive and culturally relevant, with short films, group discussions and role-playing. Each session begins with a “dicho,” or saying, in Spanish. The trainings draw on real-life examples to help parents understand how they can participate in their children’s early development to produce long-term success in academics and physical and emotional health.

One of the reasons Abriendo Puertas, which is being taught across the country, works so well is that it empowers parents to take control of their children’s development and make important decisions on that basis. One session teaches parents what to look for at different stages of development, including fine motor stills, cognitive development and language development, and to recognize if there is a problem. During that session, one of the mothers spoke up. She said her son wasn’t talking at the age he was supposed to, but that his pediatrician had assured the family that he was fine. “The child is now behind in school, and she’s thinking it’s because she didn’t push her pediatrician harder on the language development,” says Alston. Puente is trying to enroll the boy in Homework Club to help improve his literacy skills.

Reading together at the library.

What if parents are shy about second-guessing authority figures? One of the sessions focuses on advocacy – teaching parents about their rights in the context of working with school administrators, as well with doctors and landlords. They also learn about the rights of their children.

Most of the sessions focus on ways to reinforce literacy at home. Even if parents themselves are not literate and can’t read to their children in Spanish (or English) they can still make up stories, ask questions, make observations. They can turn off the TV and go for a walk together. Everyday actions, like grocery shopping, are great opportunities for interaction.

“The message is, we want you to talk to your child. You don’t need to be an expert. When you ask your child, ‘What sweater do you want to wear, the red one or the blue one?’ Right there is early literacy,” says Alston.

In 2014, Puente received a grant from the Heising-Simons Foundation to fund its new Family Engagement Impact Initiative, which Puente developed in conjunction with the La Honda-Pescadero Unified School District. The two-year, nearly $400,000 grant has already helped Puente launch several efforts designed to address students’ struggles by promoting early literacy and bridging the learning gap between home and school. One of the first efforts was to expand Raising a Reader, a free book-bag program, to the younger grades while teaching their parents how to read books to their children – even if they themselves don’t know all the words. Forty-four parents of preschool and kindergarden students (75% of all parents of that age range) participated in Raising a Reader Family Nights. The second major program Puente implemented was Abriendo Puertas.

Two younger participants in Abriendo Puertas play at the library in Half Moon Bay.

The sessions also cover difficult topics like disciplining children without yelling or hitting. Parents are introduced to the concept of positive discipline, and get some good tips on how to enforce consequences for misbehavior. “That was one of the sessions when parents were at the edge of their chairs, really paying attention,” recalls Alston.

Iris Fernandez, Mental Health Intern at Puente, is teaching a session on emotional health in the home. It all starts with modeling good communication, she says. Sometimes parents explode when they’re sad or angry, and then they’re surprised when their children do the same. Or sometimes children bottle up their feelings because they don’t have the language to express them.

“We know as a community there’s a lot of trauma, depression, drugs, domestic violence. So it can be eye-opening for parents to see they can make changes if needed,” says Fernandez. Parents are key in their children’s social-emotional development. When children have positive, respectful and loving relationships, they learn to express and regulate their emotions in a positive way.“There’s a dicho: ‘Cada cabeza es un mundo.’ Every head is its own world. We can’t imagine that everyone will react in the same way to the same circumstances. It’s okay to be mad or sad. It’s okay to express whatever tension there is, but in a safe way. Children learn this from adults who can model positive interactions.”