Manuel Santamaria visited Puente de la Costa Sur for the first time in 1999. He had just joined the Peninsula Community Foundation, one of two organizations that later merged to form Silicon Valley Community Foundation. He was there to learn more about this new organization from its founder, Rev. Wendy Taylor.

He wasn’t expecting what he found: “third world” conditions for field workers who had inadequate housing, poor sanitation, and no health care safety net. Many Mexican-American families in the area suffered similar deprivations.

“There was no formal infrastructure there to help people,” says Santamaria, now Director of Grantmaking with Silicon Valley Community Foundation. “Folks didn’t have access to many of the health and human services offered ‘over the hill’ not to mention adult education, like night classes if they were trying to learn English. The men worked in the fields, the women stayed home, and the kids went to school.”

As part of its grantmaking strategy to facilitate immigrant integration, Silicon Valley Community Foundation supports community groups whose emphasis is on opportunity and equality. Santamaria, like Rev. Taylor, saw an important opportunity in Pescadero. That year, the community foundation gave Puente its first major seed grant to establish a strategic plan and an operating budget.

This year, Puente celebrates 15 years of serving as the South Coast’s community resource center. Puente has evolved into a crucial service hub with a $1.7 million budget and a regional reach that extends far beyond Pescadero to La Honda, Loma Mar and San Gregorio.

It would be hard to imagine that reality without the steadfast support of Silicon Valley Community Foundation, says Puente Executive Director Kerry Lobel. “They’ve supported us every step of the way,” she says. “Puente was a tiny footbridge before, and now it’s an enormous span. SVCF provided the bricks and mortar on both sides of that bridge.”

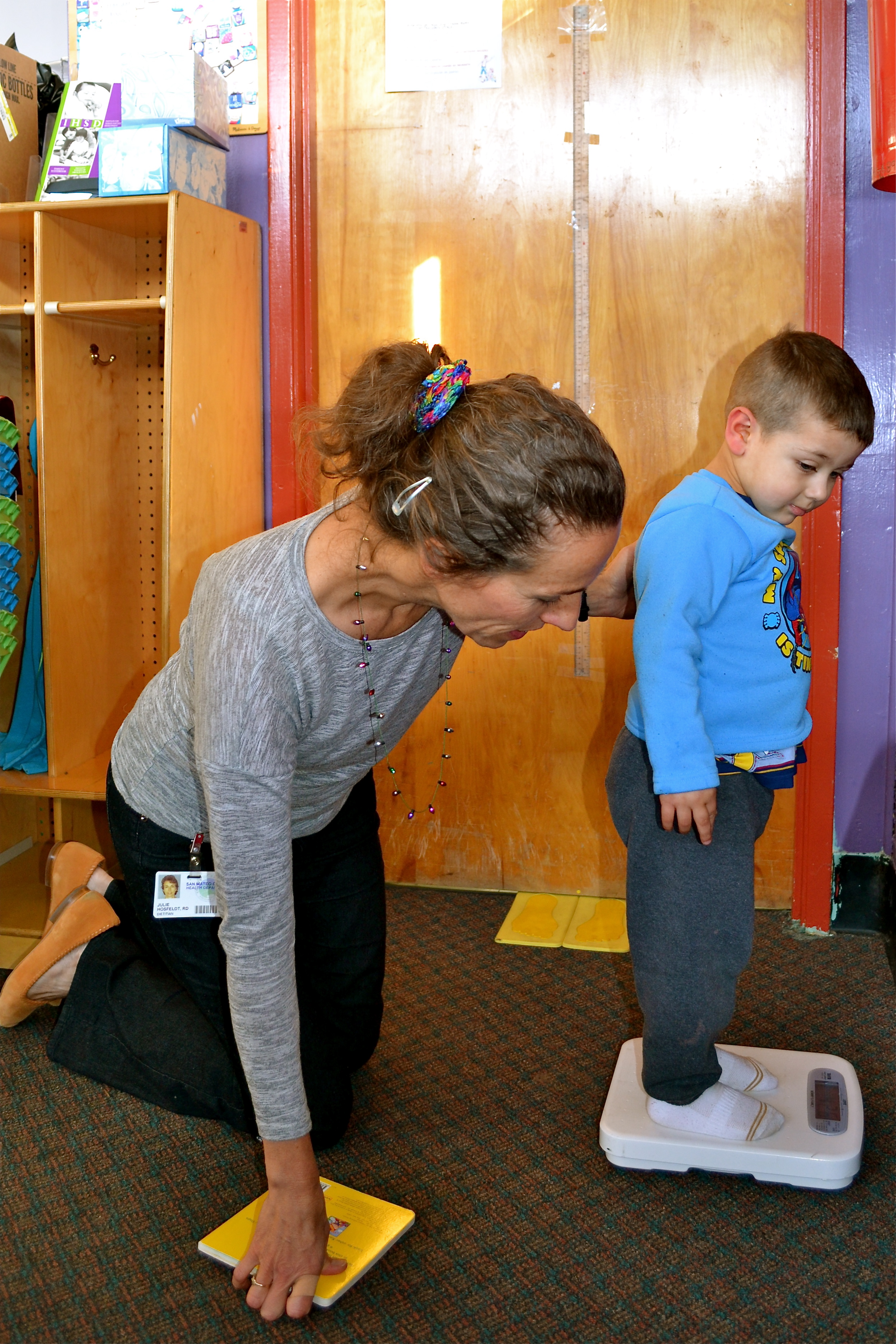

Lobel also likens SVCF to a godparent that has stepped in to support and guide Puente during some of its most important milestones. SVCF gave Puente its first flexible ‘safety net’ funding. The community foundation supported an early medical program that helped Puente enroll uninsured adults, and the first mobile health van in Pescadero. It funded one of the first local pre-kindergarten programs. SVCF helped underwrite the costs of Puente’s merger with North Street Community Services in 2007, a move that gave Puente the tools to survive the recession.

The Peninsula Community Foundation (one of SVCF’s parent organizations, along with Community Foundation Silicon Valley) even predated Puente as a primary stakeholder in the development of services on the South Coast. The South Coast Collaborative, a working group of residents, organizations and human service providers, benefited from the support of the Peninsula Community Foundation as early as 1997.

Santamaria estimates that since 2004, Puente (and the South Coast Collaborative) have received more than $1.3 million in grant funds from the community foundation and its donors.

In 2012, Silicon Valley Community Foundation and its donors supported Puente’s programs and services with funds totaling $158,000. Funds from SVCF currently support Puente’s adult education program; a benefits analyst position to help locals enroll in the Cal Fresh (food stamps) discount program; and health care services for local youth. When a large fire displaced several Mexican-American families earlier this year, SVCF donors rallied to help them pay their rent and buy clothes. They even got one student a new computer. Starting next year, Puente will have to look elsewhere for safety net support. But SVCF may support Puente’s expanded immigration and legal services, according to Santamaria.

It’s rare for a nonprofit to benefit from the kind of opportunities SVCF has given Puente, according to Lobel. The community foundation has challenged Puente to build its own capacity during difficult times, but has also supported the organization as it has grown and matured.

“I think we have grown, just as they have grown,” says Lobel. “There’s a feeling they’re in it with Puente for the long haul.”

To donate to Puente, visit https://rally.org/puente. To learn more about volunteering with Puente, contact Abby Mohaupt at amohaupt@mypuente.org or (650) 879-1691.