The new mobile health clinic is a hard-won solution to a systemic lack of reliable health care on the South Coast. Here is a timeline of previous approaches to this problem.

Late 1970s / Early 1980s: Following advocacy efforts by a group of local women, San Mateo County begins providing free, regular well-baby check-ups in the Pescadero Community Church. The county provides a Nurse Practitioner, and many local women also volunteer.

1994 Members of the community purchase a mobile health truck and park it near the Pescadero Community Church. Health providers take over well-baby check-ups; provide family planning and other services. In the late 1990s, the truck also visits local farms and ranches.

1995 County facility opens in Half Moon Bay with limited adult primary care, public health, and mental health services. Rotacare offers weekly urgent care services in County location through community volunteers and local funding.

2002 South Coast Collaborative gets foundation funding to pay County to staff a part-time public health clinic, based at the South Coast Community Center located at Pescadero Elementary School. The County sends the mobile van to La Honda for the first time ever. This service was discontinued in 2004.

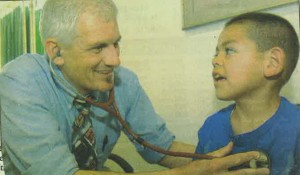

Dr. Ben Boblett performs a checkup on 4 year-old Valentin Lopez, marking the 1st anniversary of El Sol de Clinica. May, 2005.

2007 Puente and North Street merge; Puente continues funding for comprehensive mental health care program, which continues to this day. These services were first begun and initially funded in 2000 by two Healthy Start grants and other foundation funding obtained by the South Coast Collaborative.

2007 New public health nurse, Frances Sanchez-Anderson, placed in Pescadero. The County also re-funded a mobile health van, which made weekly visits to Pescadero.

2008 Closure of Pescadero branch of Coastside Family Medical Clinic.

2009 County ceases funding for mobile health clinic and public health nurse, due to budget constraints.

2009 Closure of Half Moon Bay main branch of Coastside Family Medical Clinic.

2012 San Mateo County Health System renovates and reopens a Coastside Clinic in Half Moon Bay, to expand primary care health services.

2012 San Mateo County Board of Supervisors approves funding for full-time South Coast Public Health Nurse — Karen Hackett placed at Puente.

2013 San Mateo County voters pass measure A. Board of Supervisors authorizes funding for South Coast Medical Clinic.