Most people who work in this country earn wages, pay for expenses and file taxes in a conventional way: they deposit paychecks into a bank account, write checks, use credit cards to make large purchases, and file taxes using their Social Security number.

But millions of foreign nationals in the U.S. live a shadow life when it comes to financial conventions. They file taxes using an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number, or ITIN, in place of a Social Security number. Since some local banks still require a Social Security number to open a bank account, they are unbanked, and must handle everything in cash. Not having a bank account also means no credit card and no credit history. It requires a tremendous amount of extra energy and clever workarounds just to be able to get by.

That’s true of Dorotea Garcia and her partner Alonso (not their real names), who have both filed their taxes with Puente for several years, using an ITIN. They accrue few, if any, benefits in return for their efforts. But as they will tell you, it’s the right thing to do.

“My partner has always said that he wants to do the right thing, the correct thing. And that it’s important for us to report what we earn,” says Garcia. It’s a sentiment she agrees with.

Puente’s free, year-round tax program assists more than 100 clients a year – anyone making less than $55,000 a year can qualify. Of that number, roughly half of the people file their taxes using an ITIN.

Garcia came to Pescadero 20 years ago from Oaxaca. She has three children born here, ages 19, 16, and 8. She works in a plant and flower nursery. She would like to be able to deposit her paychecks in a checking account, open a savings account, and have a credit card.

“I’ve never used a bank account to save my money. I handle all my money in cash – to pay the rent, to assist my daughter with school expenses, to buy groceries,” she says.

Twice a month, when she earns a paycheck, the whole family drives to Half Moon Bay or Santa Cruz so that Garcia can cash it somewhere, like a grocery store. Some stores take a big bite out of her paycheck to cash it – she’s lost as much as $30 per transaction. And that’s not the only problem.

“Pretty much every big expense is off limits. We’ve tried to finance many things, but we couldn’t get them because of credit. We tried buying a used car – they didn’t let us because we didn’t have credit. We tried to buy a fridge or our home, and a TV. And they denied us as well, because we didn’t have credit,” she says.

In the end, the family had to economize and save enough to pay for the appliances in cash. For the car, they had to ask a family member to finance it, and then repaid the debt in installments, in cash.

Puente made financial literacy a priority in anticipation of a time when a local bank could welcome everyone regardless of their legal status. Two years ago, Puente partnered with the Mission Asset Fund to teach all the basics to people who had never set foot in a bank.

Participants learned about savings accounts and checking accounts. They talked about what a budget looks like. What debit cards and credit cards are, and how they work.

“People are learning how to do mobile banking. They feel comfortable and confident. When they open a bank account they will know how to manage their savings rather than walking around with cash,” says Ortega. He’s preparing to help participants open bank accounts online, although some may choose to drive to a bank branch.

“Now we’re talking with San Mateo Credit union to provide some further financial education to cover these and other financial topics with youth and adults,” he added.

Garcia says having a bank will be a huge help to the entire family. It’s a relief, in fact.

“I’ll end up saving a lot of money in the long run, having a bank account where I can go and cash my check without having anything deducted from it,” she says. “But the main thing for a bank account is to save in case of an emergency. And maybe it could help me build credit too.”

This also has been a bruising tax season. The new tax rules have shifted the amount that many lower-income participants owe in federal income taxes, based on the number of exemptions they claim on their W-4 tax forms.

Someone who may have owed $200 or $300 in prior years now finds themselves owing $1,000 or even $1,500 – an astronomical amount to anyone earning the minimum wage.

“I’ve assisted these participants in previous years, and this year they’ve owed a lot more.

It’s like, how are they going to pay for it? They can’t believe it. It’s hard for them to understand,” says Ortega. He’s helping people establish payment plans with the IRS, and he’s advised them on how to lower the number of deductions they claim next year.

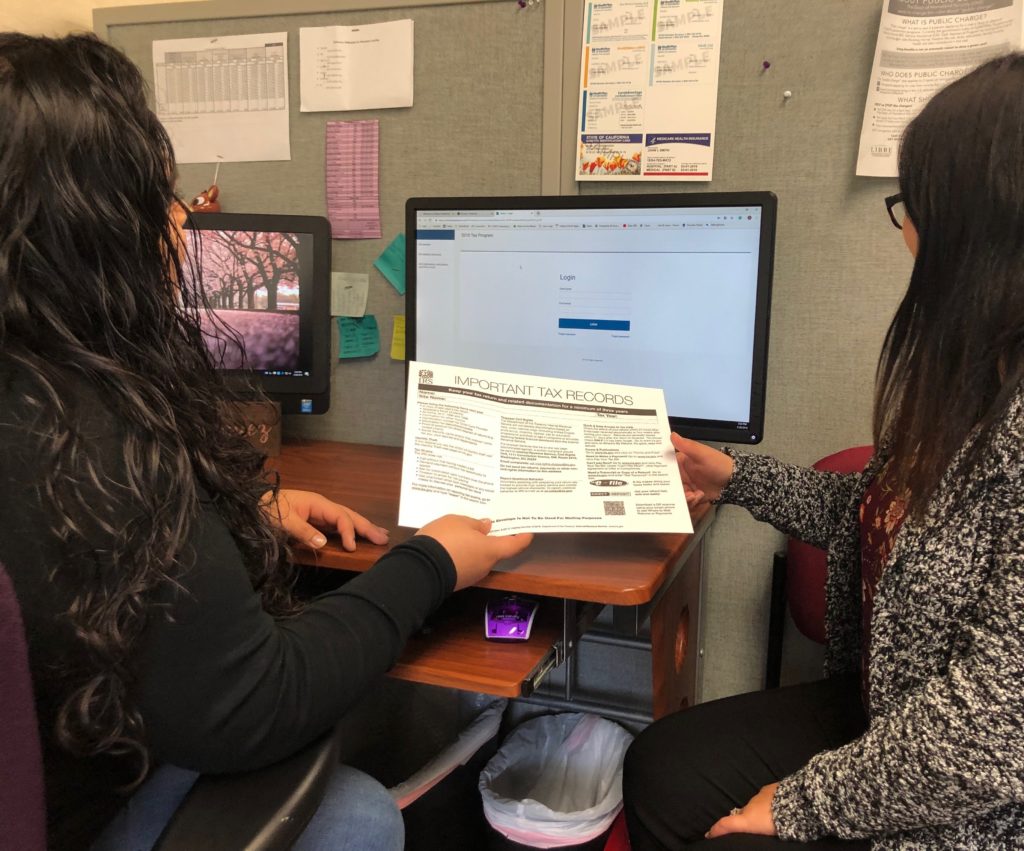

Overall, Ortega spends at least two visits with an individual or couple filing their taxes. If their situation is complicated, it’s common for him to spend hours on the phone with the IRS on their behalves. He prefers being able to tell clients that they can expect a refund, when possible.

In the last 11 years, Puente has filed a total of 784 tax returns and helped clients earn $1,046,788 in refunds. For tax year 2017, Puente helped clients earn $155,318 in refunds — the highest earned refund amount since the launch of Puente’s tax program in 2008.

When it comes to taxes or spending, Garcia believes that knowledge equates to power.

“Unfortunately, a lot of people in my community don’t have this financial education and we need to have more resources to be better informed,” she says.

Puente’s free tax preparation program is offered in partnership with the Earn It, Keep It, Save It Coalition and funded by United Way of the Bay Area and the Silicon Valley Community Foundation. This program serves anyone in the South Coast Community who earned last year $55,000 or less. If you would like to support our Safety Net program, please consider donating today.

Puente complementa sus servicios de preparación de impuestos con educación financiera.

La mayoría de las personas que trabajan en este país ganan salarios, pagan sus facturas, preparan y pagan sus impuestos de una manera convencional: depositan cheques de pago en una cuenta bancaria, escriben cheques, usan tarjetas de crédito para realizar grandes compras y presentan impuestos utilizando su número de Seguridad Social.

Pero millones de ciudadanos extranjeros en los Estados Unidos todavía tienen muchas limitaciones cuando se trata de convenciones financieras. Presentan los impuestos utilizando un Número de Identificación de Contribuyente Individual, o ITIN, en lugar de un número de Seguridad Social. Dado que algunos bancos locales todavía requieren un número de Seguridad Social para abrir una cuenta bancaria, no cuentan con servicios bancarios y deben manejar todo en efectivo. No tener una cuenta bancaria también significa no tener tarjeta de crédito ni historial de crédito. Esto requiere una tremenda cantidad de energía extra y soluciones inteligentes para poder sobrevivir.

Eso es cierto para Dorotea Garcia y su pareja Alonso (no son sus nombres reales), quienes han presentado sus impuestos a través de Puente por varios años, usando un ITIN. Ellos acumulan pocos o ningún beneficio a cambio de sus esfuerzos. Pero como dicen ellos, lo hacen porque es lo correcto.

“Mi pareja siempre ha dicho que hay que hacer lo correcto. Y que es importante para nosotros declarar lo que ganamos,” dice García. Es un sentimiento con el que ella está de acuerdo.

El programa de impuestos gratuito de Puente asiste a más de 100 clientes al año; cualquier persona que gane menos de $55,000 al año cualifica para este programa. De ese número, aproximadamente la mitad de esas personas que preparan sus impuestos utilizando un ITIN.

García llegó a Pescadero hace 20 años desde Oaxaca. Ella tiene tres hijos nacidos aquí, de 19, 16 y 8 años. Trabaja en un vivero de plantas y flores. A ella le gustaría poder depositar sus cheques de nómina en una cuenta corriente, abrir una cuenta de ahorros y tener una tarjeta de crédito.

“Nunca he usado una cuenta bancaria para ahorrar mi dinero. Yo manejo todo mi dinero en efectivo: para pagar el alquiler, para ayudar a mi hija con los gastos de la escuela, para comprar comestibles,” dice ella.

Dos veces al mes, cuando recibe su cheque de nómina, toda la familia conduce a Half Moon Bay o Santa Cruz para que García pueda cobrarlo en algún lugar, como una tienda de comestibles. Algunas tiendas le cobran una cuota de su cheque por cobrarlo, hasta $ 30 por transacción. Y ese no es el único problema.

“Casi todos los grandes gastos extraordinarios están fuera de su alcance. Tratamos de financiar muchas cosas, pero no podemos obtenerlas debido a falta de crédito. Intentamos comprar un automóvil usado, pero no nos dejaron porque no teníamos crédito. Intentamos comprar una nevera o nuestra casa, y un televisor. Y ellos también nos negaron, porque no teníamos crédito,” dice ella.

Al final, la familia tuvo que economizar y ahorrar lo suficiente para pagar los aparatos en efectivo. Para el automóvil, tuvieron que pedirle a un miembro de la familia que lo financiara, y luego pagaron la deuda en cuotas, en efectivo.

Puente hizo de la educación financiera una prioridad hasta que un banco local les pudiera dar la bienvenida a todos sin importar su estado legal. Hace dos años, Puente se asoció con el Mission Asset Fund para enseñar un curso básico de finanzas a aquellas las personas que no han puesto nunca un pie en un banco.

Los participantes aprendieron sobre cuentas de ahorro y cuentas corrientes. Hablaron de cómo se hace o lee un presupuesto, qué son las tarjetas de débito y de crédito y cómo funcionan.

“La gente está aprendiendo a hacer banca móvil. Se sienten cómodos y seguros. Cuandoabran sus cuentas bancarias, sabrán cómo usarlas en lugar de andar con dinero en efectivo,” dice Ortega. Se está preparando para ayudar a los participantes a abrir sus cuentas en línea, aunque algunos pueden optar por conducir a la sucursal bancaria.

“Ahora estamos hablando con la cooperativa de crédito para proporcionar más educación financiera para cubrir estos temas con jóvenes y adultos,” agregó.

García dice que tener un banco será de gran ayuda para toda la familia. Es un alivio, de hecho.

“Terminaré ahorrando mucho dinero a largo plazo, teniendo una cuenta bancaria donde pueda ir y cobrar mi cheque sin tener que deducir nada de eso,” dice ella. “Pero lo principal este tener una cuenta bancaria para ahorrar en caso de una emergencia. Y tal vez podría ayudarme a construir un historial de crédito también.”

Esta ha sido una temporada de impuestos bastante dura, según Ortega, quien supervisa el programa de impuestos de Puente. Las nuevas reglas impositivas han cambiado la cantidad que muchos participantes de bajos ingresos adeudan en los impuestos federales sobre la renta, según el número de exenciones que reclaman en sus formularios de impuestos W-4.

Alguien que podía deber $200 o $300 en años anteriores ahora debe pagar $1,000 o incluso $1,500, una cantidad astronómica para cualquier persona que gana un salario mínimo.

“He ayudado a estos participantes en años anteriores, y este año han debido mucho más.

Y ellos piensan, ¿cómo lo van a pagar? No pueden creerlo. Es difícil para ellos entender, ” dice Ortega. Está ayudando a las personas a establecer planes de pago con el IRS, y les ha aconsejado cómo reducir las deducciones que reclaman el próximo año.

En general, Ortega pasa al menos dos visitas con un individuo o una pareja que presenta sus impuestos. Si su situación es complicada, es común que pase horas al teléfono con el IRS. Prefiere poder decirles a los clientes que pueden esperar un reembolso, cuando sea posible.

En los últimos 11 años, Puente ha presentado un total de 784 declaraciones de impuestos y ha ayudado a los clientes a ganar $ 1,046,788 en reembolsos. En el año fiscal 2017, Puente ayudó a sus clientes a recibir $155,318 en reembolsos, el monto más alto de reembolso ganado desde el lanzamiento del programa de impuestos de Puente en 2008.

Cuando se trata de impuestos o gastos, García cree que tener conocimiento equivale a tener poder.

“Desafortunadamente, muchas personas en mi comunidad no tienen esta educación financiera y necesitamos tener más recursos para estar mejor informados,” dice ella.

Los servicios gratuitos de preparación de impuestos de Puente son ofrecidos en collaboración con la Earn It, Keep It, Save It Coalition y fundado por United Way of the Bay Area y el Silicon Valley Community Foundation. Este programa ayuda a los residentes de la Costa Sur con ingresos de menos de $55,000. Si le gustaría apoyar al programa de servicios de salud económica haga su donación hoy.