Something that struck me immediately when I met Puente Adult Education Coordinator Charlea Binford is the way she puts her entire self into the task at hand. Without fail, you can count on Charlea to be fully emotionally and intellectually invested in whatever project she’s working on. And it shows completely when it comes to her students, who threw her a surprise birthday party, who stop by the office for hugs, or who call her when they need an ear. I know all of this is true because I have a pretty good vantage point – I sit right behind Charlea at Puente!

So it was no surprise that despite some initial trepidation about teaching driver license courses, she has embraced the challenge and it has now become one of her favorites. She remembers when Puente first asked her to take this on, thinking, “Am I really qualified to do this? There is SO much Spanish I need to learn not to mention the rules of the road!”

But Charlea voraciously prepared, reading the Spanish and English manuals side-by-side as many as 6 times, wearing out a few highlighters in the process. “Now I pretty much have the thing memorized,” she laughs.

Puente began supporting participants who wanted to get their driver’s license last year after implementation of AB60, a California state law which allows undocumented immigrants to get a license and drive legally in this state. AB60 has helped our community members come out of the shadows and we are thrilled to help them along the way. The classes that Charlea teaches are part of our commitment to prepare students for the exam.

“I was so nervous before my first class, but now it’s the one I feel most comfortable teaching.” Learning English in an ESL classes is very much an ongoing process, but the driver license class has a clear end-goal, which makes the teaching a little bit different – not to mention that the entire class is taught in Spanish. But some aspects are the same. “That first class is always so important,” says Charlea. “You have to have fun, engage people and help them realize they should be here,” which is also true for ESL.

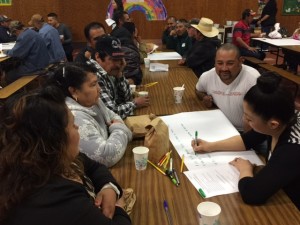

The classes we have at Puente are designed to prepare participants to pass the written exam. So far all but one student of Charlea’s have accomplished that goal.

The in-class preparation complements a car safety course that Charlea teaches; student learn how to change a tire and what emergency tools they should keep in their car.

Charlea helps a student change a tire.

But the final bit of support Charlea provides? She accompanies many students to the DMV to take their exams. “My general experience as a Puente employee is talking to people about their fears, whether it’s a GED test, learning English or how to navigate the DMV. The DMV is scary for most people, but it’s scarier if you don’t speak English. I have experienced so many uncomfortable moments of ‘Charlea, I failed my test’ that I’ve really honed in how to react to that response.”

On the long drive to the DMV, Charlea reviews passing signs and challenging concepts she knows from experience give people trouble on the exam—one more chance for the student to prepare for the exam. To calm nerves at the DMV, she congratulates participants for “passing” the vision exam: “You passed your first test!” The participant usually responds with a nervous laugh. “My job is to make them feel comfortable and prepared,” Charlea recalls.

They are on their own in the testing area, and many do not pass on their first of three tries. “Almost always it’s because of nerves. I calmly take them aside and explain to them that they know the information, but their nerves aren’t letting their brain get to the information,” she says. Almost everyone passes by the third try. “One participant didn’t need any help from me but just needed my presence, and with that, she nailed it.”

It’s particularly tense watching the written exam be graded. And when the employee announces they passed—well, it “is such an intimate moment. It fills me up so much to go through such a vulnerable, nervous experience and it’s such a breath of fresh air when they know they’ve passed. On the way home we can talk about anything and everything – you always feel closer. I just feel so lucky that it’s my job to do it.” On the way home there is usually a stop for ice cream or candy to celebrate.

When asked what she does if the participant doesn’t pass, Charlea said, “Then we still go for ice cream!” with a big smile.

As lucky as Charlea feels that this is her job, our participants feel just as lucky to have her in their lives. And as her colleague I can say the exact same thing.

To learn more about the importance of drivers licenses on the South Coast, listen to this story.