(Para ver la traducción en español de esta historia, desplácese hacia abajo de la pagina).

Three Puente participants become U.S. citizens – and voters

This fall, Puente celebrated three local green card holders who completed their journey to becoming citizens of the United States – just in time to vote in the 2022 midterm election.

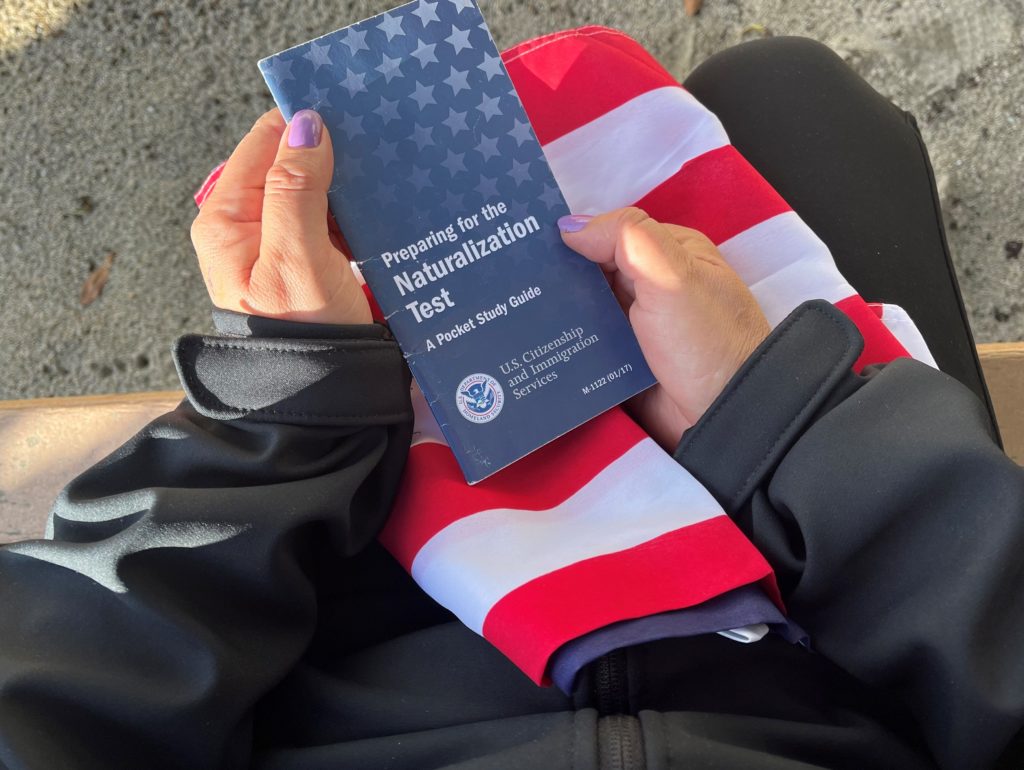

Puente helped the participants fill out all their forms and submit their citizenship applications free of charge. Puente also helped them study for the naturalization interview and the civics test by providing study materials or connecting them with volunteer tutors.

It was a lengthy, stressful challenge for all three, who began the application process more than a year before they were sworn in. All are local parents who have lived on the South Coast for more than a decade, and all were born in Mexico. One other thing they have in common: a deeply-held belief in the importance of voting, and an interest in politics.

“We’re happy about this outcome, and especially that it also just happened to be around the midterms,” says Corina Rodriguez, Puente Community Development Director. Rodriguez is part of a two-person Puente team, with her colleague Laura Rodriguez, who have special Board of Immigration Appeals accreditation to support immigration cases.

Miguel, a male participant who became a U.S. citizen this past July, specifically approached Rodriguez about wanting to exercise his right to vote.

“He said, “Hey, I’ve noticed that there’s a lot of conversations around voting for the local school board members, and I have two kids in school and I want to vote. How can I do that?’ And I, of course, helped him sign up,” says Corina. Miguel’s name has been changed for this story.

Not all U.S. green card holders who are eligible for citizenship choose to go through that process. Corina says that Miguel and the two other newly-minted citizens, both women, were all content to hold green cards for years. She and other Puente staff would regularly encourage them to apply, but they weren’t ready.

“Everyone has their own thing going on in their lives, and they know when it’s best for them to apply. And we respect that,” she says.

The civics test involves quite a lot of study, she adds, and it can represent a particularly nerve-wracking challenge for participants who work full time, have had limited schooling or test-taking experience, or all of the above.

Nationwide for 2022, the U.S. is on track to exceed the 855,000 new U.S. citizens it welcomed in 2021. More than nine million U.S. immigrants are eligible to apply for citizenship, but fewer than a million do so each year.

Citizenship confers significant financial benefits beyond being able to vote. Studies show that it can lead to higher earnings overall. It also opens up a category of U.S. public sector jobs, and possible U.S. employment overseas.

A big challenge leads to citizenship for Trina

Voting was on Trina Navarro’s mind when she finally applied for citizenship after 27 years living in Pescadero. She raised her U.S.-born daughter, now 23, on her salary working in local agriculture and the service industry.

“I would see how my daughter and my nephews and nieces, who were born here, would just sort of let their right to vote disappear, and sometimes skip voting. And so for me, it’s important that I know that this is my right as a citizen. I live here, and this is something I should do,” she said in a recent interview. Trina’s name has been changed for this story.

Born in Oaxaca, Mexico, Trina received a U.S.visa in 2007. That was enough for her for a long time. She was acutely aware of the oral test requirement for citizenship, wherein applicants need to memorize the answers to 100 questions about the U.S. government and politics. On the day of the test, the immigration officer will ask up to 10 questions, and at least 6 of the answers must be correct.

It all seemed like a massive undertaking for someone like her.

“Where I grew up, there was no school. I got here when I was 13 years old. When I was 16, I taught myself to read and write. And to this day, verbs and just language in general are challenging for me,” Trina says.

But when she reached her forties, she decided to push herself to try. Trina is a youthful-looking, thoughtful woman who has overcome significant obstacles in her life. Even though she worried about failing her citizenship test, she could still remember how diligently she taught herself to become literate as a teenager.

“I knew that this process was going to be challenging, and I still decided to do it. At first this was all really stressful for me, and I felt like I wasn’t going to make it. But there was always my own tutor who was telling me, You can do it! You’re going to do it! And that really helped me push through the process,” says Trina.

Interestingly, Trina made a decision early on not to tell anyone in her family that she was applying for citizenship, including her daughter, sister and other family who live with her. She met up with her tutor – a friend of hers – outside the house, and studied for the civics test at night.

“I have always felt like I don’t want to push people to be excited for me,” she explains. “I have always been the kind of person who is there for you and for others. When we’re ready to celebrate, whatever it is, we’re going to celebrate. But I have always felt excluded from that, and this was a challenge that I set for myself.”

The day of the test arrived, and Trina’s anxiety spiked as she drove to the San Francisco U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services offices. But the interviewing officer eventually set her at ease, and she aced both the test and the interview.

“I felt like I could finally breathe. I was super happy. I realized that I had overcome yet another challenge that had come along for me,” Trina recalls. “I was very proud of myself, and I felt the need to celebrate myself. So I took myself out for sushi!”

No one in Trina’s family knew about her doing the interview, and to this day, no one knows that she passed. Some weeks afterward, she also went to her swearing-in ceremony alone. She acknowledges, though, that she will have to tell them eventually.

“I’m not sure how they will feel about it, but they had previously said that I would get celebrated with a carne asada and a family gathering once I came back with the good news and the paperwork stating that I was a citizen.”

The important thing, she says with great pride, is that “I decided to do it. And I met the challenge. I did it. I became a citizen.”

When voting isn’t a birthright

For Corina Rodriguez, immigration work is personal. She gained plenty of experience handling immigration paperwork long before she became certified to do so at Puente. She often found herself renewing her parents’ or other family members’ green cards.

Corina’s mother arrived in the U.S. as a farmworker with no legal status. She got a green card in the 1980s through the immigration reform bill that President Ronald Reagan signed into law, which made any immigrant who’d entered the U.S. before 1982 eligible for amnesty.

As a girl, Corina remembers the whole family pitching in to help her mother study for her U.S. citizenship test. On weekends, while cleaning the house, the family listened to the CD with the 100 civics questions. “I would be pretty annoyed,” Corina jokes. “But we were proud of her.”

Corina’s mother is a local school employee, and casting a vote for the school board – her boss’s bosses – is important to her. Over time, Corina has come to appreciate everything her mom went through to gain that right to vote.

“We hear about it all the time from our participants: the experience of literally crossing the border and risking their lives, risking everything, leaving everything behind in Mexico,” she says. “I’m so grateful that my parents decided to do that, even before they had a family. It’s like they knew somehow that coming to the U.S. is what would be best for their family in the future. I’ve never had to go through anything like that,” she adds.

And Corina remembers the swearing-in ceremony for her mom, which she and her brother attended. “It truly did feel so welcoming,” she says.

These days, Puente’s immigration staff hears a lot of questions from local green card holders who have seen major delays in their green card renewals process due to COVID-19. Due to backlogs at the USCIS (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services), officials are automatically extending the validity of Green Cards by 24 months for lawful permanent residents who file their application to renew their green card, according to Corina.

“For several participants, USCIS has been able to reuse their previous biometrics, it saves people the extra step of having to go in to do their fingerprints again, but the whole process has slowed down,” she explains.

Some participants are getting letters from the government that ‘extend’ their existing green cards for up to two years. The problem is that the green cards themselves are expired, which is causing confusion for people who now have to carry the letter and the expired green card with them when they use their green card to travel.

“Many of our participants are calling us and saying, ‘I haven’t gotten my green card!’ And then we have to explain that they need to read the letters,” says Corina.

COVID-19 was also a factor in creating a backlog for citizenship applications following a shutdown of in-person U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) services at all branch offices in 2020.

Corina’s team is already helping a new participant apply for citizenship – a woman who jumped on her application the moment she could, as soon as the minimum five-year waiting period for holders of green cards was over. She told Corina that she wanted to vote.

“We love to see that level of enthusiasm,” says Corina. “I only wish more of our participants would embrace the same opportunity. They have lived in the U.S. for so long, and a lot of them know so much about politics. I wish they could participate more.”

We appreciate the support from our partners who support our Immigration services at Puente and those who have partnered with us to help participants get ready for their citizenship tests. Please consider supporting this and other Puente services through our end of year campaign and make a gift today!

——————————————————————————————————

Tres participantes de Puente se convierten en ciudadanos estadounidenses y votantes

Este otoño, Puente celebró a tres titulares de tarjetas verdes locales que completaron su viaje para convertirse en ciudadanos de los Estados Unidos, justo a tiempo para votar en las elecciones de mitad de período de 2022.

Puente ayudó a los participantes a completar todos sus formularios y enviar sus solicitudes de ciudadanía de forma gratuita. Puente también los ayudó a estudiar para la entrevista de naturalización y el examen de educación cívica brindándoles materiales de estudio o conectándolos con tutores voluntarios.

Fue un desafío largo y estresante para los tres, quienes comenzaron el proceso de solicitud más de un año antes de prestar juramento. Todos son padres locales que han vivido en la Costa Sur durante más de una década y todos nacieron en México. Otra cosa que tienen en común: una creencia profunda en la importancia de votar y un interés en la política.

“Estamos contentos con este resultado, y especialmente porque resultó ser alrededor de las elecciones de medio término”, dice Corina Rodríguez, Directora de Desarrollo Comunitario de Puente. Rodríguez es parte de un equipo de dos personas en Puente, con su colega Laura Rodríguez, quienes tienen una acreditación especial de la Junta de Apelaciones de Inmigración para apoyar casos de inmigración.

Miguel, un participante que se convirtió en ciudadano estadounidense en julio pasado, se acercó específicamente a Rodríguez para querer ejercer su derecho al voto.

“Él dijo:” Oye, me he dado cuenta de que hay muchas conversaciones sobre votar por los miembros de la junta escolar local, y tengo dos hijos en la escuela y quiero votar. ¿Cómo puedo hacer eso?’ Y yo, por supuesto, lo ayudé a inscribirse”, dice Corina. El nombre de Miguel ha sido cambiado para esta historia.

No todos los residentes permanentes que viven en los Estados Unidos, que son elegibles para la ciudadanía eligen pasar por ese proceso. Corina dice que Miguel y los otros dos ciudadanos recién nombrados, ambas mujeres, se contentaron con tener su residencia permanente durante años. Ella y otros miembros del personal de Puente los alentaban regularmente a postularse, pero no estaban listos.

“Todos tienen sus propias cosas en sus vidas, y saben cuándo es mejor para ellos presentar la solicitud. Y lo respetamos”, dice.

La prueba de educación cívica implica mucho estudio, agrega, y puede representar un desafío particularmente estresante para los participantes que trabajan a tiempo completo, han tenido una educación limitada o experiencia en la realización de exámenes, o tienen una combinacion de varios obstáculos.

A nivel nacional en 2022, los Estados Unidos está en camino de superar los 855,000 nuevos ciudadanos estadounidenses en 2021. Más de nueve millones de inmigrantes estadounidenses son elegibles para solicitar la ciudadanía, pero menos de un millón lo hace cada año.

La ciudadanía confiere importantes beneficios financieros más allá de poder votar. Los estudios muestran que puede conducir a mayores ganancias en general. También abre una categoría de empleos en el sector público de los Estados Unidos y posibles empleos en el extranjero.

Un gran desafío conduce a la ciudadanía para Trina

Votar estaba en la mente de Trina Navarro cuando finalmente solicitó la ciudadanía después de 27 años viviendo en Pescadero. Crió a su hija nacida en los Estados Unidos, quien ahora tiene 23 años, Trina comenzó ganando un salario trabajando en la agricultura local y la industria de servicios.

“Veía cómo mi hija y mis sobrinos y sobrinas, que nacieron aquí, simplemente dejan desaparecer su derecho al voto y, a veces, dejan de votar. Entonces, para mí, es importante que sepa que este es mi derecho como ciudadana. Vivo aquí y esto es algo que debo hacer”, dijo en una entrevista reciente. El nombre de Trina ha sido cambiado para esta historia.

Nacida en Oaxaca, México, Trina recibió una visa estadounidense en 2007. Eso fue suficiente para ella durante mucho tiempo. Estaba muy consciente del requisito de prueba oral para la ciudadanía, en el que los solicitantes deben memorizar las respuestas a 100 preguntas sobre el gobierno y la política de los Estados Unidos. El día de la prueba, el oficial de inmigración hará hasta 10 preguntas y al menos 6 de las respuestas deben ser correctas.

Todo parecía una meta enorme para alguien como ella.

“Donde crecí, no había escuela. Llegué aquí cuando tenía 13 años. Cuando tenía 16 años, me enseñé a leer y escribir. Y hasta el día de hoy, los verbos y el lenguaje en general son un desafío para mí”, dice Trina.

Pero cuando llegó a los cuarenta, decidió esforzarse para intentarlo. Trina es una mujer reflexiva de aspecto juvenil que ha superado obstáculos en su vida. A pesar de que le preocupaba reprobar su prueba de ciudadanía, aún podía recordar cuán diligentemente aprendió a leer y escribir cuando era adolescente.

“Sabía que este proceso iba a ser desafiante, y aún así decidí hacerlo. Al principio todo esto fue muy estresante para mí y sentí que no iba a lograrlo. Pero siempre estaba mi propio tutor que me decía: ¡Tú puedes hacerlo! ¡Lo vas a hacer! Y eso realmente me ayudó a impulsar el proceso”, dice Trina.

Curiosamente, Trina tomó la decisión desde el principio de no decirle a nadie de su familia que estaba solicitando la ciudadanía, incluida su hija, hermana y otros familiares que viven con ella. Se reunió con su tutor, un amigo suyo, fuera de la casa y estudió para el examen de educación cívica por la noche.

“Siempre he sentido que no quiero presionar a la gente para que se emocione por mí”, explica. “Siempre he sido el tipo de persona que está ahí para ti y para los demás. Cuando estemos listos para celebrar, sea lo que sea, vamos a celebrar. Pero siempre me he sentido excluida de eso, y este fue un desafío que me propuse a mí misma”.

Llegó el día de la prueba y la ansiedad de Trina se disparó mientras manejaba hacia las oficinas de los Servicios de Ciudadanía e Inmigración de los Estados Unidos en San Francisco. Pero el oficial de entrevistas finalmente la tranquilizó, y superó tanto la prueba como la entrevista.

“Sentí que finalmente podía respirar. Estaba súper feliz. Me di cuenta de que había superado otro desafío que se me había presentado”, recuerda Trina. “Estaba muy orgullosa de mí misma y sentí la necesidad de celebrarme. ¡Así que salí a comer sushi!”.

Nadie en la familia de Trina sabía que ella hizo la entrevista y, hasta el día de hoy, nadie sabe que pasó su examen. Algunas semanas después, ella también fue sola a su ceremonia de juramento. Ella reconoce, sin embargo, que eventualmente tendrá que decírselo.

“No estoy segura de cómo se sentirán al respecto, pero anteriormente habían dicho que me celebrarían con una carne asada y una reunión familiar una vez que regresara con las buenas noticias y el papeleo que indicaba que era ciudadano”.

Lo importante, dice con mucho orgullo, es que “decidí hacerlo. Y acepté el desafío. Lo hice. Me hice ciudadana”.

Cuando votar no es un derecho de nacimiento

Para Corina Rodríguez, el trabajo de inmigración es personal. Obtuvo mucha experiencia en el manejo de trámites de inmigración mucho antes de obtener la certificación para hacerlo en Puente. A menudo se encontraba renovando las tarjetas de residencia de sus padres u otros miembros de la familia.

La madre de Corina llegó a los Estados Unidos como trabajadora agrícola sin estatus legal. Obtuvo una tarjeta verde en la década de 1980 a través del proyecto de ley de reforma migratoria que el presidente Ronald Reagan convirtió en ley, que hizo que cualquier inmigrante que hubiera ingresado a los EE. UU. antes de 1982 fuera elegible para la amnistía.

Cuando era niña, Corina recuerda que toda la familia colaboraba para ayudar a su madre a estudiar para su examen de ciudadanía estadounidense. Los fines de semana, mientras limpiaban la casa, la familia escuchaba el CD con las 100 preguntas de educación cívica. “Me enfadaría bastante”, bromea Corina. “Pero estábamos orgullosos de ella”.

La madre de Corina trabaja en una escuela local y votar por la junta escolar, los jefes de su jefe, es importante para ella. Con el tiempo, Corina ha llegado a apreciar todo lo que pasó su madre para obtener el derecho al voto.

“Lo escuchamos todo el tiempo de nuestros participantes: la experiencia de literalmente cruzar la frontera y arriesgar sus vidas, arriesgarlo todo, dejarlo todo atrás en México”, dice ella. “Estoy tan agradecida de que mis padres decidieron hacer eso, incluso antes de tener una familia. Es como si supieran de alguna manera que venir a los Estados Unidos es lo mejor para su familia en el futuro. Nunca he tenido que pasar por algo así”, agrega.

Y Corina recuerda la ceremonia de juramento de su mamá, a la que asistieron ella y su hermano. “Realmente se sintió tan acogedor”, dice ella.

En estos días, el personal de Puente escucha muchas preguntas de los residentes permanentes que han visto grandes retrasos en el proceso de renovación de su tarjeta verde debido a COVID-19. Debido a los retrasos en el USCIS (Servicios de Ciudadanía e Inmigración de EE. UU.), los funcionarios están extendiendo automáticamente la validez de las tarjetas verdes por 24 meses para los residentes permanentes legales que presenten su solicitud para renovar,, según Corina.

“Para varios participantes, USCIS ha podido usar sus datos biométricos anteriores, les ahorra a las personas el paso adicional de tener que volver a tomar sus huellas dactilares, pero todo el proceso se ha ralentizado”, explica.

Algunos participantes reciben cartas del gobierno que “extienden” sus tarjetas de residencia existentes hasta por dos años. El problema es que las tarjetas verdes en sí están vencidas, lo que está causando confusión para las personas que ahora tienen que llevar consigo la carta y la tarjeta verde vencida cuando usan su tarjeta verde para viajar.

“Muchos de nuestros participantes nos llaman y dicen: ‘¡No he obtenido mi tarjeta verde!’. Y luego tenemos que explicarles que deben leer las cartas”, dice Corina.

COVID-19 también fue un factor en la creación de una acumulación de solicitudes de ciudadanía luego del cierre de los servicios en persona del Servicio de Ciudadanía e Inmigración de los Estados Unidos (USCIS) en todas las sucursales en 2020.

El equipo de Corina ya está ayudando a una nueva participante a solicitar la ciudadanía: una mujer que aprovechó su solicitud en el momento en que pudo, tan pronto como terminó el período de espera mínimo de cinco años para los titulares de tarjetas verdes. Le dijo a Corina que quería votar.

“Nos encanta ver ese nivel de entusiasmo”, dice Corina. “Solo desearía que más de nuestros participantes aprovecharán la misma oportunidad. Han vivido en los Estados Unidos durante tanto tiempo y muchos de ellos saben mucho sobre política. Ojalá pudieran participar más”.

Agradecemos el apoyo de nuestros socios que respaldan nuestros servicios de Inmigración en Puente y aquellos que se han asociado con nosotros para ayudar a los participantes a prepararse para sus pruebas de ciudadanía. ¡Por favor considere apoyar este y otros servicios de Puente para nuestra campaña de fin de año y haga una donación hoy!