In the parallel universe version of their lives, the one where they are U.S. citizens instead of an undocumented couple working and raising their children, Pescadero resident Cristobal Santos is a well-paid long-distance truck driver and his wife Maria is a preschool teacher’s assistant. They’re almost middle class. They take cheerful family road trips with their three kids. They explore all the places they’ve dreamed of, like New York City and Disneyland.

In the black-and-white reality of the Santos’ lives today, Cristobal is a maintenance worker and Maria works at a flower nursery, the same jobs – long hours, minimum wage – that they have had held for a decade and the only ones they can get using invalid Social Security numbers. Their three young children are Americans, born here in the U.S., but they haven’t seen much of this country. The family, whose names have been changed, has never driven farther than Reno, Nevada.

“We might hit a checkpoint. We might not be able to come back,” says Cristobal, a round-faced, compact man with a quick laugh and a direct way of speaking.

That’s their reality, crystallized: the daily fear, alongside all of life’s other concerns, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement will one day discover that the Mexican couple is working without papers, and deport one or both of them – splitting the family in two.

So they stay close to home. Watch their backs. Pay their taxes, and try to avoid contact with police and other law enforcement. Drive to school, drive to work. On weekends, they call their Mexican relatives, whom they haven’t seen in 12 years and their kids have never laid eyes on.

“My kids are like, ‘Why can’t we see our grandparents? Why don’t we know them?’ I tell them, and then they say, why don’t you have documents?’” says Maria, who wears a ponytail and speaks sadly.

They live like coiled springs. They don’t really talk about it anymore. It’s gone on for so long now that the feeling of apprehension is part of the background of their daily lives.

“It’s like a room. You have everything but you can’t leave,” says Cristobal, simply.

It looked like things might change in November 2014 when President Obama announced DAPA, the Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents program, an executive order providing temporary protection from deportation and a work permit.

It’s not a path to citizenship, but for the Santos family and 4.9 million other unlawful immigrants whose children are U.S. citizens, and who have already been living and working here for years, it would offer a form of state-sanctioned legitimacy and a huge relief from the constant fear of deportation.

“I want to live freely. And I want my social services. There’s 12 million of us here and where is that money going?” says Cristobal.

But those hopes were dashed when a Texas judge stymied the Obama order with a temporary injunction blocking both DAPA and a proposed extension of DACA. Their lawyers have argued that the federal government does not have standing to enact such a sweeping reform. The case is now before an appeals court in New Orleans, which heard arguments in July. It is widely expected to reach the Supreme Court.

“It’s been the biggest letdown of our whole year that our government isn’t ready and we’ve been ready,” says Kerry Lobel, Executive Director of Puente.

For months, Puente has been poised to process DAPA applications for more than 120 estimated local residents who would be qualified to apply. Within weeks of President Obama’s DAPA announcement, Puente staff members personally reached out to each of them, distributed flyers and scheduled a community information session. Puente assembled packets to help parents collate all the legal papers, including proof of residency and work history, which would be needed to help them apply. Eighty such packets are now in circulation.

Puente has invested more than 200 staff training hours to prepare five staff members to assist participants with their DAPA applications and other immigration legal needs. Puente Deputy Executive Director Rita Mancera was the first staff member to receive legal worker accreditation, and Puente obtained Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) agency recognition this summer.

The message now is about staying hopeful and prepared. “It’s taking a long time, but we keep telling people where things are,” says Mancera.

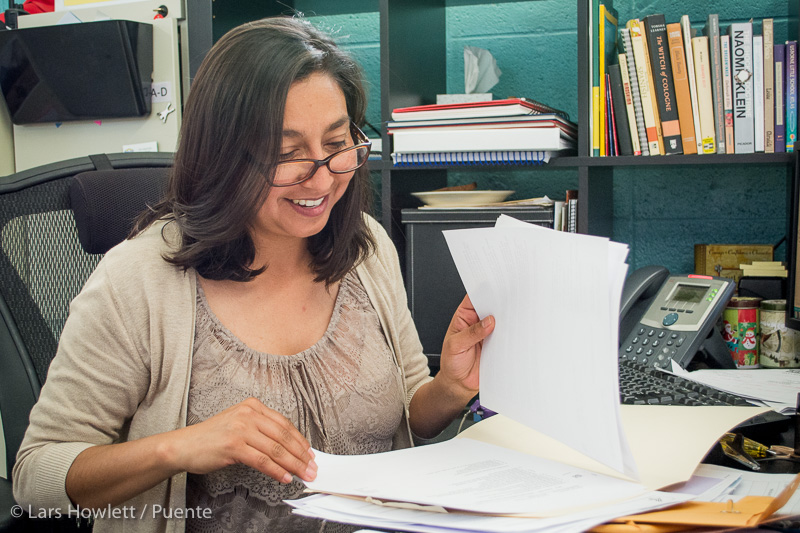

Mancera at work at Puente.

The Santos family is prepared – their packets are complete because they gathered all their papers within months of the announcement, back when they thought DAPA was imminent. But Maria Santos is no longer hopeful.

“I really believe it’s not going to happen,” she says. “For one reason or another, it’s always being postponed. It’s sad, because when we first heard about DAPA we thought it was going to change everything, and so far it’s all words and promises.”

Supporters see DAPA as a common-sense extension of DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, a federal initiative that since 2012 has awarded work permits to roughly 100,000 previously undocumented residents who were brought to the U.S. as children).

More than 20 youth on the South Coast have received their work authorization since Puente started processing DACA applications for free in 2012, and the resulting opportunities have transformed their lives in remarkable ways.

Jack Holmgren, California Legalization Director of the Catholic Legal Immigration Network, is troubled by the lawsuit that has halted DAPA and sabotaged what he sees as “a ray of light” for people.

Holmgren helped guide Puente staff members through the BIA training and accreditation process which his nonprofit provided.

“This is part of Puente’s immigrant integration strategy. Their goal is to see that the community as a whole gets to a better place, so immigrant and native-born alike can prosper.”

The good news, says Holmgren, is that with its BIA recognition, Puente won’t entirely have to wait around for the federal government to move forward. It can do screenings with people who want to see whether they can benefit from DAPA. Participants may even discover they are qualified to apply for a visa or may find a different path to citizenship.

“It’s that old phrase, ‘Knowledge is Power.’ Now the information that people may have something going for them will make all the difference,” says Holmgren.

Here in California, some families have earthquake disaster plans. The Santos family has a deportation-survival plan.

“We have talked about it. If I’m deported and the children are left behind here, they would be raised without a father,” says Cristobal Santos. “If one of us is deported, we’ve decided we would all go to Mexico.”

Their children would be yanked out of school and transplanted to a rural village in Mexico. “It’s another life there…. of poverty,” he adds.

Cristobal has more hope for the future than his wife.

“Obama had good intentions, but unfortunately the Republicans don’t support us. It will not happen in a year, but maybe in three years,” he says. “Now we just have to wait and hope. Not be desperate. And stay out of trouble.”