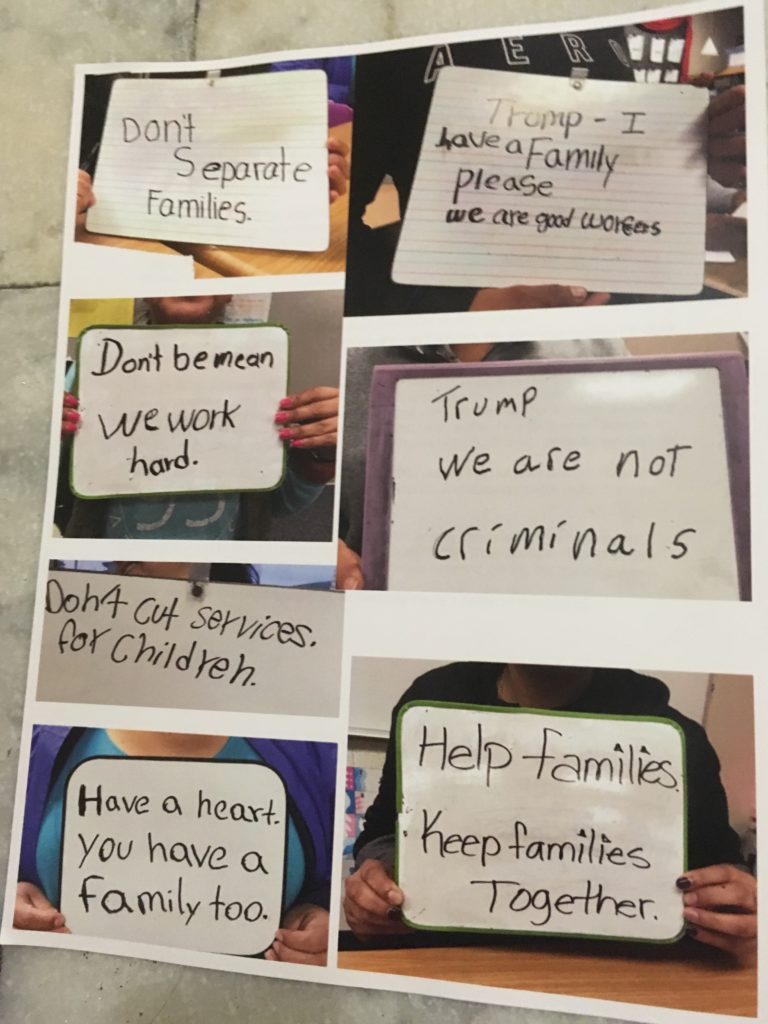

Photo collage of the ESL students’ messages

Undocumented, but not unrepresented:

Puente ESL students raise their voices in Washington

Shortly after President Donald Trump was sworn into office in January, Puente ESL instructor Kit Miller hit on an idea for how to make her students’ voices heard in the new political environment, beyond their classroom in rural Pescadero.

Miller, a veteran English language instructor with a lifelong commitment to activism around women’s rights and immigration issues, proposed an experiment that combined English language learning and self-advocacy.

“I feel I’m in a unique position to help people speak out. I know how to reach out to Congress,” she says.

With Puente’s blessing, Miller invited the students in her mixed-level ESL class – Mexican women in their 30s and 40s – to tell their personal immigration stories. She also invited them to compose letters and messages to their local political representatives in Sacramento and Washington.

“It’s so easy to see the everyday effect of our terrible policies on the people I teach. What people miss is the positive impact these people make inside their industries. They are contributing to our world and our country and they have something to say. They have skills. Puente realizes that,” says Miller.

Many of Miller’s students, both documented and undocumented have a high degree of anxiety for themselves and their families in Trump’s America. She reasoned that this was a way of taking their energy to an actionable level, and to practice their English at the same time.

It was an emotionally risky writing prompt, because it was the first time the women had ever written their own stories. Yet they eagerly embraced the assignment. They shared the truths about their treacherous border crossings and their difficult lives in Mexico. One student revealed that both her parents were killed when she was 10 years old. Students also wrote about the challenges and rewards of their lives in Pescadero, where many of them have started their own families.

“I’ve had people cry in class,” says Miller. “It’s hard for them to think about their parents – they haven’t seen their moms in 15 or 20 years. Yet there must be something kind of therapeutic about putting it down and having people know it happened.”

Miller’s assignment – which was voluntary – also called for a dose of bravery. Many undocumented students chose to write letters to their elected representatives on the topic of immigration reform. They also wrote short messages on a dry-erase board, which Miller photographed. Some of the letters and messages were anonymous. Nevertheless, in some cases, students wanted to be identified.

The messages were touchingly simple and direct. “Don’t be mean – we work hard.” “Don’t cut services for children.” “Don’t separate families.”

Miller assembled a photo collage of the messages into a document, along with an edited version of students’ personal stories. On a lobbying trip to Washington, D.C. with a group of women activists, Miller presented the document to Congresswoman Anna Eshoo (D-Palo Alto). Eshoo’s reaction was heartfelt.

“She practically started crying. She was so emotional,” says Miller. She said, ‘My parents were refugees. This means so much to me. Tell your students I’m going to put this near my door so anyone who walks by can read this.’

And she did. Eshoo also sent a letter of commendation to each student in Miller’s class, a big surprise they received at their ESL graduation.

Lizeth Hernandez, Education Director for Puente, says Puente could not be happier.

“I think the atmosphere and the political climate called for an outlet for our students, and Kit provided that. One of the components at Puente is self-advocacy, and what better way for students to voice their opinions, to testify to their presence? It was saying, ‘We’re here and you can’t treat us like this.’ I think it’s beautiful.”

The class exercises had a profound effect on many students. “I felt proud of that certificate [from Eshoo]. We wrote these letters, and this person took the time to go over them. I felt like a very important person,” says Lupita (who did not want to use her last name).

Lupita is an ESL student whose personal story included a harrowing account of her border crossing several years ago. It took her three tries to get across la linea. On her second attempt, her clothing got caught on the barbed wire fence – her brother made it through, and he tried, and failed, to pull her through with him. She was arrested, jailed, and released back to Mexico.

But nothing could stop Lupita from trying to reach Pescadero, where her sister was living. Her family in Oaxaca was so poor that they slept in a house made of adobe with no door. As a girl, she would imagine coming to the U.S. because she wanted to buy a door for her family.

“Writing my story was a highlight for me. Another one was writing a letter to the congresswoman,” says Lupita. “I said to her: ‘Please do not separate the families. Don’t discriminate against the farm workers, because we are the ones that work the field.”

Margarita (last name also omitted) had an arduous border crossing 23 years ago, when she was just 18. She had to jump over a very high wall and wade across a powerful river to get to Nogales, Arizona. She promised her parents in Guanajuato, who begged her not to go, that she would return in three years’ time. But she met her future husband in Pescadero, and they started a family of their own.

Her four children are her life now. Deciding to stay means that she has not seen her parents in 23 years. It is profoundly painful to think she may never see them again. They are in their 60s now and they both have a heart condition.

“In my letter, I asked the politicians to be there for us. To pass immigration reform for us… so that maybe someday we can actually get back to Mexico and hug our parents again,” says Margarita.

The election outcome traumatized Margarita’s children, who were all born here – especially her 10-year-old daughter. “She started crying, saying she didn’t want her parents to be deported. And every time she hears something about the subject, she says she doesn’t want to be taken to Mexico. She wants to stay here.”

Margarita and her husband have assured their daughter that nothing bad will happen. But quietly, they have tried to work out a plan for what to do if their children were suddenly parent-less. It’s almost impossible to conceive.

Margarita believes in the power of a personal story to touch the heart. One thing she liked is that Eshoo’s letter told the class that if any of them ever have problems with immigration, they could reach out to her local office in Palo Alto.

“I think it was worth writing the letter for that,” she says with a laugh.

Both women are fired up by their first brush with activism. They plan to start organizing on behalf of immigration rights, and they are not taking ‘no’ for an answer.

“I will continue to fight – not just for us, but for everyone who’s in same positon as we are,” says Margarita.

“We plan to go to the senators’ offices, and to our neighbors’ houses. We’ll be going house by house if we need to,” adds Lupita. “I would like to lobby for a law that could actually help immigrants get to see their families. It’s not just women, but men also who came to this country and left their families behind.”

“Yes,” echoes Margarita. “I think the class gave us more strength to continue to fight, and continue to write, to continue to bring out our feelings.”

Please consider supporting Puente’s Adult Education and ESL Programs today. These are not only vital services for South Coast residents, but also community empowerment initiatives that unify our community, and elevate the voices of those most vulnerable.