First generation Latino students can find themselves at a disadvantage in school. Their parents, many who emigrated from Mexico, may not yet speak enough English or have the formal schooling to help their children with homework, as is often expected by teachers. Even their own language skills and background can be challenged on a daily basis. When students finish high school, the prospect of obtaining a college degree and pursuing a career can feel a bit like going to another world. If they choose the college path, they are headed somewhere no one in their families has been before. And it can require an act of genuine imagination for both student and parents.

A new Puente educational programming grant from the Sand Hill Foundation turns students’ backgrounds into an asset to be cultivated, not a liability – especially their language abilities. The Sand Hill support supplements earlier grants from Philanthropic Ventures Foundation and the Access to Achievement Foundation. Puente Academic Director Suzanne Abel is using the $35,000 grant – which was awarded in December – to help improve academic outcomes for Pescadero High School and Middle School students, most of whom are Latino.

Abel recently spearheaded a partnership with Stanford University, which enrolled Pescadero youth in the Stanford College Prep summer program and a year-long interdisciplinary Introduction to Latin American Studies through the SAAGE (Stanford Academic Alliance for Global Enrichment) initiative of the Center for Latin American Studies.

Puente has already teamed with the La Honda-Pescadero Unified School District and nearby universities to put the grant to work in support of several initiatives, including planned programs designed to bolster biliteracy in creative ways; bring parents into their children’s academic lives; and break the isolation of living on the South Coast by exposing students to college campuses and programs focused on meeting the needs of first generation students.

For the first time, this May 3, graduating seniors at Pescadero High School will be awarded the State of California’s Seal of Biliteracy. Many students are already bilingual, serving as de facto translators and interpreters for their parents, yet they may not recognize the career potential of refining these remarkable skills. The state’s Seal of Biliteracy is the first in the nation, a model that now has been adopted by New York State.

“They can put the recognition on their resumes. It’s something amazing to offer on the job market, and most of them take it for granted without fanfare,” says Abel.In the wider world, some students may feel they need to hide their Spanish and their ethnic backgrounds in order to succeed. In reality, these students represent the face of a more globalized America: the Latino population alone is projected to grow from 16% to 30% of the US population by 2050, presenting a systemic challenge to public education but also tremendous opportunity.

“It’s a strange aspect of our national myth that immigrants should leave their country of origin and first language behind in order to become ‘American’,” Abel says. “Arguably, that made some sense at the turn of the 20th Century, but in today’s connected world, the ability to navigate more than one language and culture is a tremendous advantage.” According to Abel, sadly, too often immigrants’ Spanish is perceived as a deficit or a problem.

Projects like these have been possible thanks to the enthusiastic participation of the La Honda-Pescadero Unified School District (LHPUSD), which has the challenge of bringing Spanish-speaking students up to par in English in order to excel. Pescadero High School Principal Pat Talbot says she couldn’t be happier.

“I think the Seal of Biliteracy is fabulous! It puts being bilingual in such a positive way, and one that will only enhance students’ opportunities for the future,” says Talbot. “Since this award is so new, it also puts us on the ‘cutting edge,’ so to speak.”

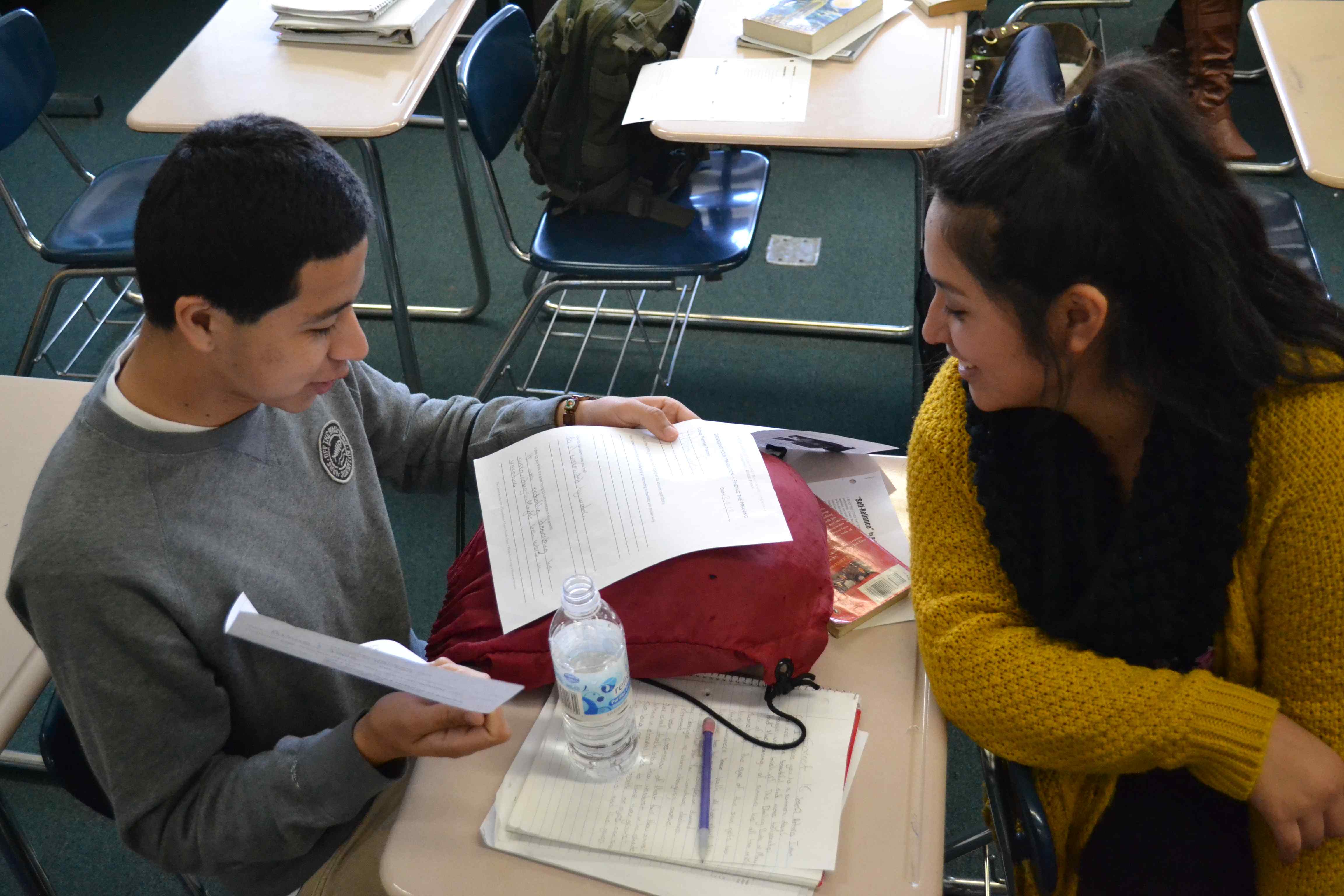

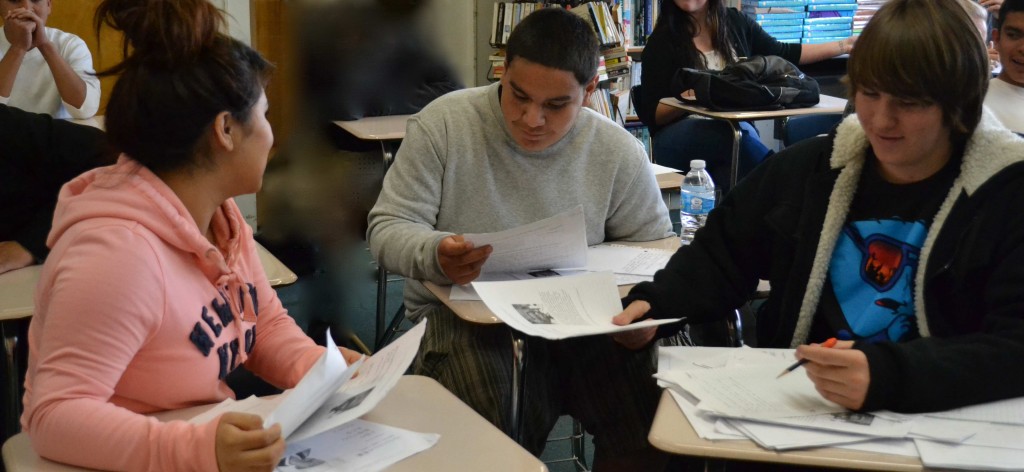

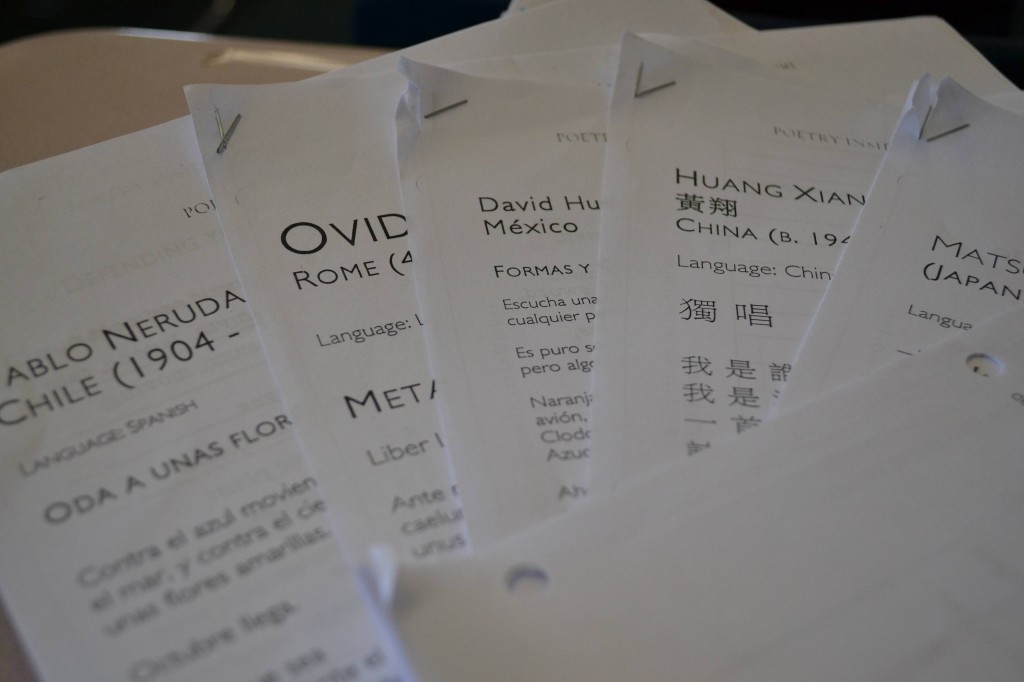

This year, three teachers also started using the Poetry Inside Out (PIO) curriculum, a program of the Center for the Art of Translation in San Francisco. PIO gives students a poem written in a foreign language and walks them through a process of translating the poem first into English, literally line-by-line, and then another version with creative juices flowing. Students have to debate and defend their word choices, and engage with the complexities of both languages.

Puente introduced the program to the school district, hosting a 2-day training led by Dr. Marty Rutherford and her colleague, Mark Hauber, which was attended by LHPUSD staff and by bilingual specialists from the San José Unified School District. At their core, so many of the academic challenges in the school district derive from communication issues — that’s what Abel has concluded since coming to work for Puente.

For instance, because many local parents have only a few years of schooling and minimal exposure to English, they have difficulty understanding what happens in local schools (especially beyond the elementary grades) and therefore struggle to be strong advocates for their children.

Among other uses, Puente will apply Sand Hill Foundation grant funding to bilingual summer “math camp” workshops for Latino parents through the school district, and to expand Puente’s parenting class series to include more sessions focused on understanding the U.S. education system so that parents can better support their children.

Finally, on May 17, Puente will hold its second annual “First Generation Careers Night” for prospective college students and their parents. Bilingual speakers from a wide range of careers will share their own stories of immigration, education, and the path to meaningful work, as part of Puente’s evolving approach to opening the doors of possibility to more Pescadero students and their families.