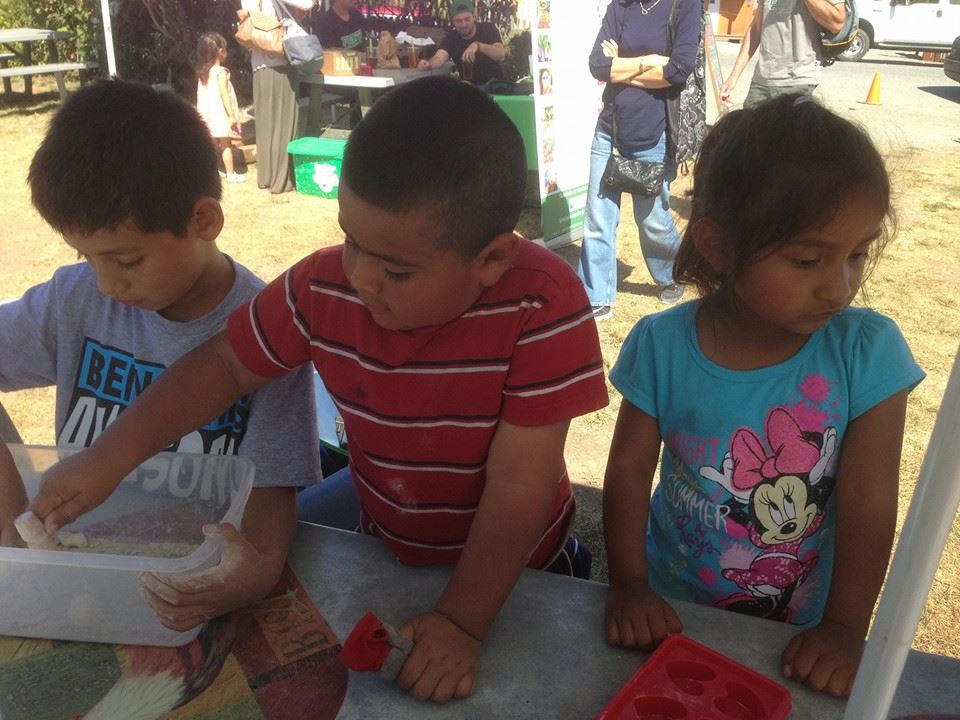

Photo by Ellen McCarty

“Every time we sit at a table to enjoy the fruits and grain and vegetables from our good earth, remember that they come from the work of men and women and children who have been exploited for generations.” Cesar Chavez

March 31st marks Cesar Chavez Day, which recognizes the contributions of a man who looked around, saw injustice, spoke out, organized, and resisted. The resistance of countless farmworkers resulted in the founding the United Farm Workers Union, or UFW, in 1962. Consumer boycotts and farmworkers’ organizing eventually led to better pay and safer working conditions for those who toil on the front lines of agriculture.

National Farmworker Awareness Week (NFAW) was established by Student Action for Farmworkers, in 1999 in Durham, North Carolina. NFAW (March 24-31, 2017) is an opportunity for all of us to look around, see injustice, speak out, organize, and resist. In a time when we care deeply about what we eat, we can easily refuse to see the men, women, and children who grow our food. At the very least, we need to reflect about the individuals who feed this country.

History – “We used to own our slaves, now we just rent them.”

In 1960, the famous journalist, Edward R. Murrow, helped produce a documentary called Harvest of Shame, which focused on the plight of the migrant farm worker in the US at the time. In the film, one farmer makes the chilling statement above, effectively characterizing farm labor as modern day slavery.

In the United States, we expect food to be cheap and plentiful, and it is easy to see where that expectation comes from. For hundreds of years, farmers were able to bring cheap, plentiful crops to market because they had slave labor. The tough reality—154 years after President Lincoln freed the slaves in the South—is that the expectation of cheap, plentiful food remains. That means that feeding this country today still depends on a hardworking, very low earning labor force of farmworkers. Over 70% of that labor force is comprised of immigrants, according to the 2013-2014 National Agricultural Workforce Survey (NAWS). Immigrants are often the only ones willing to do the hard work necessary to maintain that stream of cheap, plentiful food.

National context

“Work hard and you can get ahead” is core to what we think of as “The American Dream.” That dream does not reflect reality if you are a farm worker. Federal laws of the Depression era 1930s specifically excluded farmworkers from provisions that provided for overtime pay, minimum wage, unionizing rights and workplace protections. The 2013-2014 NAWS reported that farmworkers’ mean and median incomes from agricultural employment the previous year were in the range of $15,000 to $17,499. Sixteen percent of workers earned less than $10,000; only eight percent in the United States earned $30,000 or more. Thirty percent had family incomes less than the federal poverty level. Farmworkers earned an average hourly rate of $10.19 per hour. Since the 1980’s, the costs of producing food has skyrocketed, but the real costs have not been passed on to the consumer.

The reality is that farmworker labor is physically debilitating. Workers have to work very long hours, through rain, cold and heat for extremely low wages. Federal laws continue to exempt farmworkers from overtime pay — only 35% reported having health insurance and 31% report living in crowded living conditions (NAWS, 2013-2014). Here in the United States, we can’t claim that hard work will get you ahead and then systematically exclude some of the most hardworking people from basic rights and opportunities afforded to literally every other job in this country.

In recent years, the foodie movement has put more focus on where people’s food comes from and how the animals were treated and raised. Though laudable, starkly missing from this conversation, are the people involved in producing our food. Are the workers treated with dignity and respect? Are they fairly compensated for their work? It is as if the farmworkers are invisible. They are invisible because many are undocumented and have no immigration relief available to them despite their hard work—even if their employers wish to sponsor them. Fortunately, new trends in the sustainable agriculture movement consider not only where food comes from, but also the quality of life for those that grow the food we eat. A recent study indicated that raising farmworker wages to $15 hour today would cost consumers only $21.15 a year.

Today, farmworkers in California earn about $30,000 a year if they work full time — about half the overall average pay for all California workers. Most work fewer hours. Nine in 10 agriculture workers in California are still foreign born, and more than half are undocumented, according to a federal survey.

The South Coast perspective

The legacy of Cesar Chavez lives on in our great state of California. Farmworkers contribute significantly to California’s economy, and California is the top farming state in the US. Our minimum wage is one of the three highest in the country at $10.50 per hour, with plans for it to rise to $15 per hour by 2022. California is one of few states that provide some overtime pay for farmworkers, currently after 10 hours of work per day. There was also a law passed in 2016 that will bring that threshold down to 8 hours of work, finally beginning to level the playing field for farmworkers.

Critics of these policies argue that agriculture should have its own rules because of its seasonal nature. The person who loses the most in that scenario is the frontline farmworker. Any increased labor cost to the farmer needs to be built into the cost of food. The onus must be shared by a society that needs to be willing to pay prices that reflect the true cost of food production.

Here on the South Coast, all workers are making at least minimum wage, and some farms give raises to workers after employing them for 6 months or a year. Workers are almost all paid by the hour, avoiding “pay by piece” issues that often arise when workers are instead paid by how much they harvest. Unfortunately, even though many workers have had the same jobs for 5, 10 or 15 years, they still earn only the minimum wage. The economics of our food system are complex. It is not as easy as asking farmers to raise wages. To do so, they also need to raise their prices, meaning their buyers may find someone else to buy from, which can put the entire business at risk, including the farmworkers’ jobs.

Housing remains an enormous challenge here on the South Coast. Farmworker wages cannot keep up with the exorbitant cost of rent in the Bay Area. Unable to afford market rent, many workers and their families live in crowded conditions with little or no access to necessities such as laundry facilities or public transportation.

Puente

Puente has its roots in supporting farmworkers and we continue that work today, almost 20 years later. Puente’s role has grown and evolved in this community, but farmworkers and their families still make up the backbone of the South Coast and hence remain at the core of our work. Our oldest program, La Sala, still provides a hot meal and social space for farmworkers twice each week. Additionally, our bike repair program focuses on getting farmworkers reliable transportation without having to deal with the costs associated with a car.

Our hope is that our community can be one where farmworkers and their families cannot only survive, but also thrive and flourish – despite the challenges and pressures exerted upon them by antiquated federal laws.

What can I do?

At the very least, say thank you! Farm labor is probably one of the most thankless and invisible work. Find an opportunity to connect with farmworkers and farmers in your community and make it clear you appreciate their efforts. Find out more about where your food comes from and support your local farmers market. Inform yourself about the challenges faced by farmworkers by watching films like Food Chains or Harvest of Dignity. Another very simple way to support farmworkers is to donate to Puente.

On April 4 at 7pm, join us in recognizing Farmworker Awareness Week with the screening of the film “The Other Side of Immigration” in the multi-purpose room of Pescadero Elementary, with a discussion to follow.