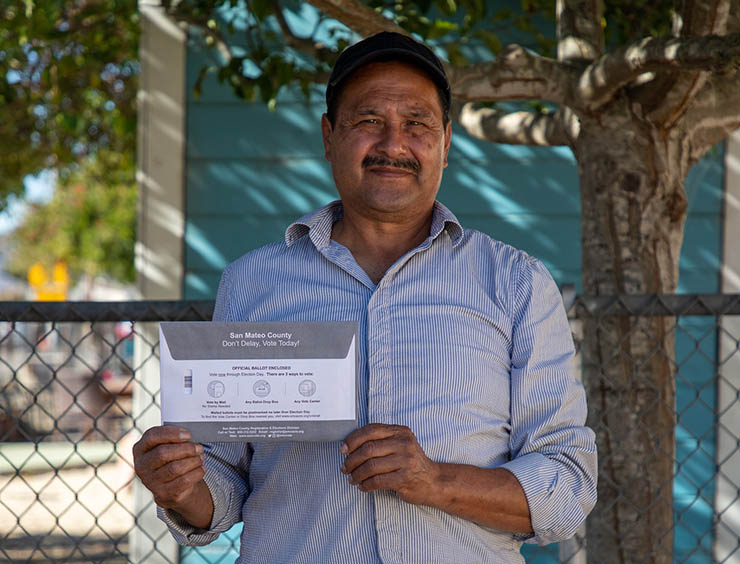

Joaquin Vargas is one of Puente’s most steadfast food distribution volunteers.

Joaquín Vargas es uno de los voluntarios de distribución de alimentos más firmes de Puente.

Rita Mancera remembers the exact day she knew Puente was in for a long ride amid the COVID-19 pandemic: March 16, when San Mateo County imposed emergency shelter-in-place requirements. Overnight, the South Coast shut down—except for essential workers including farm workers and the Puente team.

“From the very beginning, everything turned upside down. And it happened so quickly,” says Mancera, the Executive Director of Puente. Soon enough, the calls came for assistance. At first, Mancera thought people would request the items in short supply: masks, gloves, and sanitizer. But there was one thing that residents needed most of all and suddenly could not get: food.

“People started asking us, ‘Is Puente doing food distribution? And do you know where we can go for food?” she recalls.

Corina Rodriguez remembers it well. Puente’s Health and Community Development Director was nearly overwhelmed by a wave of new requests for help in all of Puente’s core safety net programs, including food assistance. At the same time, as a new mother, she also found herself struggling to locate essential grocery items for her infant daughter.

“I would go to Half Moon Bay to shop, but I couldn’t find milk for my daughter – she had just moved over from formula to whole milk. And other staff members were saying they tried to go buy eggs, but couldn’t … A lot of our staff is also from the community, so we knew we were driving 30 minutes to Half Moon Bay, only to get there and not find what we needed,” she says.

In those early days, some South Coast residents were afraid to leave their houses to go to the grocery store. This was especially true for local seniors and those with compromised immune systems, who started inquiring about a grocery drop-off or centralized distribution.

Rodriguez immediately contacted Second Harvest of Silicon Valley and arranged to join a free distribution pickup on Thursday mornings.

On March 26, Puente began its weekly food program featuring staples from Second Harvest and some basic produce from R&R Fresh Farms of Pescadero. Nearly a dozen Puente staff members got everything organized for the event. It continued on Thursdays outside the Puente offices near Pescadero Elementary.

Almost immediately, Rodriguez started hearing from other local farms and ranches who offered to step in and provide food for free or at cost. Soon Puente was able to distribute ground beef and prime cuts from TomKat Ranch, lettuce from Oku Farms, and a huge variety of fresh, seasonal vegetables and fruit from Pie Ranch.

“Second Harvest is a really great partner, but they didn’t have all the items that families in our area use to prepare their meals—like tomatoes, onions and lettuce. And at the beginning, we weren’t getting eggs either, because of the shortage,” says Rodriguez.

Rodriguez also initiated a contract with US Foods for milk, eggs, and tortillas. “It was a lot of work, but they have discounted prices for nonprofit clients. And they are great because they will come directly out here and drop off the items,” she adds.

As it launched food distribution, Puente also underwent a major internal reorganization to respond to community needs in other key areas. On April 27, Puente began accepting applications for its COVID-19 Relief Fund. It is meant to fill a major gap for undocumented and mixed status families who were left behind by the CARES Act.

At the same time, Puente was obliged to shut down its bilingual childcare co-op. Staff members found a way to shift its early childhood program into a home support model that continues to help children thrive. And Puente converted its summer Youth Leadership and Employment Program into a remotely accessible program with workshops, skill-building, mentorship and paid employment opportunities.

Puente was also inundated with requests for help filling out unemployment paperwork. Staff handled 40 applications in the first week alone, and soon started making appointments three weeks out.

“I was grateful that Puente had so much of the infrastructure ready in place to move and adapt in a really fast way,” says Mancera.

At the height of demand, an average of 200 families and individuals showed up each week to receive food from Puente.

“It was strange and shocking to see the lines of cars that went all the way down the road to Harley Farms,” Mancera recalls. “Definitely there were a lot of people who found themselves in a food line for the first time. People were saying, ‘I can’t believe I’m here… and I’m so grateful to you guys for doing this.’”

Community steps up in a big way

Joaquin Vargas is one of Puente’s most steadfast food distribution volunteers. The 37-year-old lives alone in Pescadero. He started showing up for shifts—it’s a long shift, from 12 p.m. to 6 p.m.—in March.

Vargas says he has enjoyed the work of unloading the food from bags and boxes, dividing and repacking everything that gets loaded in people’s cars from four different food stations. “But more than anything, I enjoy helping out and seeing other community members helping out, too. I like seeing people leave happily with their bags of food.”

Vargas enjoys the camaraderie, too. Working with Puente is one of the only times he gets to connect with neighbors these days.

“Helping out is in my blood,” he says. “From my childhood, there was always just enough food, the bare necessity, not extra – we always had to go look for little jobs if we wanted to buy ourselves other things we wanted. I would go help relatives out, or work for them, and they would give me a little money or they would send me home with a meal.”

Vargas has enjoyed the food he gets through Puente, especially the broccoli, tomatoes, and lettuces. But the best part has been hearing other people react to the food, and when they thank him for his help.

“It’s gratifying. I don’t have the financial means to donate, so I can help by volunteering,” he adds.

California was not the only U.S. state that experienced food scarcity in the first wave of the pandemic. If anything, the empty shelves laid bare showed just how vulnerable the whole food system was. While people on the South Coast were struggling to find milk and eggs, farmers across the country were dumping tens of thousands of gallons of milk and smashing eggs because their normal markets—restaurants, hotels and schools—were suddenly closed.

Meanwhile, communities like Pescadero, which widely relies on agricultural employers, could not readily find affordable food to feed their families.

Enter Pie Ranch, which found a solution that directly benefits farmers and struggling families throughout the Peninsula. It partnered with Fresh Approach, a Concord-based organization that gets food to communities that need it.

At the time, Pie Ranch had a surfeit of produce that was destined for programs that could no longer receive it. So, as they started streaming food into Fresh Approach, farm leaders had another idea: what if they could also aggregate surplus food from other producers around the region?

“The need was apparent when the pandemic hit. Farms were seeing a challenge for finding buyers for their food once restaurants shut down. And people were having trouble finding and paying for food, and paying their bills at the same time,” says Mona Urbina, culinary programs manager at Pie Ranch.

Very quickly, the farm spun up an entirely new distribution system that keeps farms solvent and gets food to 800 children and adults per week, including through Puente. It is funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and several foundations.

Before the pandemic, Urbina was the garden teacher at Pescadero Elementary. She ran after school cooking classes through the Food Lab program, and worked with middle and high school students, helping them make breakfast for their fellow students. She oversaw youth programming at Pie Ranch.

Now she helps direct the farm’s food relief program. She manages the pack-out, coordinates the volunteers, and ensures that everything complies with COVID-19 rules concerning social distancing and food safety.

“Being part of this solution means a lot to me—one that I hope can be a model for other farms to become an aggregate to distribute food to their communities,” she says. “It’s just one small solution for how we can adapt to these situations, like the pandemic we’re in.”

Going above and beyond

For the past decade, TomKat Ranch in Pescadero has donated 100 pounds of beef per month to the lunch program at the La Honda-Pescadero Unified School District—enough to supply two meals each month districtwide. When classes were shut down and Puente opened its food distribution, Kathy Webster saw a way to help many of the same families and the community at large.

“When the crisis hit, it seemed like the first thing to go off the shelves in grocery stores was the meat. You walked in and it was completely empty. So, access to protein, like meat, became more challenging, especially in under-sourced food areas,” says Webster, who is the Food Advocacy Manager for TomKat Ranch.

To add to that challenge, many big meat-packing houses were forced to close due to rampant coronavirus exposure. The result was a bottleneck that drove up the cost of beef almost everywhere. Even Taqueria de Amigos in Pescadero had to post a sign explaining to customers why the cost of some meat-based dishes, like carne asada, was suddenly higher.

“Here in town, we’ve already been limited by the fact that Pescadero Country Store burned down three years ago… so local access to fresh food and protein sources is already extremely limited,” Webster points out.

By the time Puente’s food distribution was in full swing, TomKat was donating up to 200 pounds of grass-fed beef per week—including ground beef, bones and high-end cuts. This has amounted to more than 2,500 pounds of meat so far, according to Webster. TomKat also donated 4,800 pounds of meat to the Alameda County Food Bank in July and August, which will equate to about 4,000 meals in total.

“We only harvest at a certain time of year. But we had some still in the freezer, plus donation meat earmarked for schools,” she explains. “We shifted our strategic plan for the year. We are dedicating a certain number of animals so that we can continue to donate to Puente every week for the rest of the year. We are super excited about that.”

TomKat’s generosity has inspired a lot of appreciation from locals, says Rodriguez. “I know that in the weeks that we got a lot of ground beef from TomKat, community members were saying, ‘I made burgers! I made spaghetti!’ It was really nice to hear that people were excited to take it home and make whatever they wanted with it.”

TomKat helped solve another big local problem: egg scarcity. A team member, Annie Fresquez, came up with the idea for a pilot program to offer local families the chance to have chicken coops near their homes, and share the resulting eggs with neighbors. Puente handled the outreach. Fifteen families agreed to take part, and TomKat built the custom coops this summer. The recipients did the final assembly.

Dede Boies at Root Down Farm agreed to raise the chicks, which were delivered in July. The program has been so popular that “we had people calling in and asking if they could get on a waitlist. Unfortunately, we don’t have any more coops,” says Rodriguez.

Sustainable in uncertain times

The South Coast has been modeling true mutual aid at its rural best. In the midst of a crisis affecting people’s health, economic resilience, education and food access, the community has created a series of remarkable outcomes.

But that is not all. Rather than simply respond with Band-Aid measures, volunteers and community members, farms and nonprofits have come together to spin up entire structural solutions that, once erected, will continue to serve residents through future crises, whatever they may be.

The coronavirus pandemic has made invisible networks visible. Not just the ways in which health care delivery and food systems are deeply vulnerable, but also the ways we get our food. The farms and ranches that provide the food. The hands that pick it, pack it, and unpack it. That knowledge represents a new possibility for resilience on a homegrown level.

“We found a new way of collaborating with the local farms. It’s powerful for locals to know that, unlike people who have to go miles to get their groceries, they can get it fresh, within a few miles of their homes,” says Mancera. “It has also been a good opportunity for our farms, particularly the organic farms. They started selling out really fast—it was like people finally noticed them in a bigger way than before.”

That includes some low-income residents, who now know about CSA boxes (Community-Supported Agriculture, essentially a subscription to a local farm).

For now, demand for food has declined enough that Puente is shifting to a more limited food distribution partnership with Pie Ranch (for fruits and vegetables) and TomKat Ranch (for meat), vouchers for the hyper-local Pescadero Growns Farmer’s Market and gift cards. Puente’s financial assistance program has returned to a habitual level of service, compared with the frenzied demand this spring.

Puente’s efforts have been possible thanks to emergency donations from foundation partners, a major donor, and the many supporters who continue to donate to Puente’s COVID-19 Relief Fund.

La ditribución de alimentos de Puente llega a 200 familias cada semana

Rita Mancera recuerda el día exacto en que supo que Puente iba a dar un largo paseo en medio de la pandemia de COVID-19: 16 de marzo, cuando el Condado de San Mateo impuso requisitos de refugio de emergencia en el lugar. Durante la noche, la costa sur cerró, a excepción de los trabajadores esenciales, incluidos los trabajadores agrícolas y el equipo de Puente.

“Desde el principio, todo se puso patas arriba. Y sucedió muy rápido ”, dice Mancera, el Director Ejecutivo de Puente. Muy pronto, llegaron las llamadas de ayuda. Al principio, Mancera pensó que la gente solicitaría los artículos escasos: máscaras, guantes y desinfectante. Pero había una cosa que los residentes necesitaban sobre todo y que de repente no podían obtener: comida.

“La gente comenzó a preguntarnos: ¿Puente está haciendo la distribución de alimentos? ¿Y sabes a dónde podemos ir por comida? ella recuerda.

Corina Rodríguez lo recuerda bien. El Director de Salud y Desarrollo Comunitario de Puente estuvo casi abrumado por una ola de nuevas solicitudes de ayuda en todos los programas básicos de redes de seguridad de Puente, incluida la asistencia alimentaria. Al mismo tiempo, como una nueva madre, también se encontró luchando por localizar artículos de abarrotes esenciales para su pequeña hija.

“Iría a Half Moon Bay a comprar, pero no pude encontrar leche para mi hija, ella acababa de pasar de la fórmula a la leche entera. Y otros miembros del personal decían que intentaron ir a comprar huevos, pero no pudieron … Gran parte de nuestro personal también es de la comunidad, por lo que sabíamos que íbamos en coche 30 minutos a Half Moon Bay, solo para llegar allí y no encontrar qué necesitábamos ”, dice ella.

En esos primeros días, algunos residentes de la costa sur tenían miedo de salir de sus casas para ir a la tienda de comestibles. Esto fue especialmente cierto para las personas mayores locales y aquellos con sistemas inmunes comprometidos, que comenzaron a preguntar acerca de la entrega de alimentos o la distribución centralizada.

Rodríguez contactó inmediatamente a Second Harvest de Silicon Valley y acordó unirse a una recolección gratuita de distribución los jueves por la mañana.

El 26 de marzo, Puente comenzó su programa semanal de alimentos con productos básicos de Second Harvest y algunos productos básicos de R&R Fresh Farms of Pescadero. Casi una docena de miembros del personal de Puente organizaron todo para el evento. Continuó los jueves fuera de las oficinas de Puente cerca de la primaria Pescadero.

Casi de inmediato, Rodríguez comenzó a escuchar de otras granjas y ranchos locales que se ofrecieron a intervenir y proporcionar alimentos de forma gratuita oa un costo. Pronto Puente pudo distribuir carne molida y cortes principales de TomKat Ranch, lechuga de Oku Farms y una gran variedad de frutas y verduras frescas de temporada de Pie Ranch.

“Second Harvest es un gran socio, pero no tenían todos los artículos que las familias de nuestra área usan para preparar sus comidas, como tomates, cebollas y lechugas. Y al principio, tampoco recibimos huevos debido a la escasez”, dice Rodríguez.

Rodríguez también inició un contrato con US Foods para leche, huevos y tortillas. “Fue mucho trabajo, pero han descontado los precios para clientes sin fines de lucro. Y son geniales porque vendrán directamente aquí y dejarán los artículos ”, agrega.

Al lanzar la distribución de alimentos, Puente también se sometió a una importante reorganización interna para responder a las necesidades de la comunidad en otras áreas clave. El 27 de abril, Puente comenzó a aceptar solicitudes para su Fondo de Ayuda COVID-19. Su objetivo es llenar un vacío importante para las familias indocumentadas y de estatus mixto que fueron dejadas atrás por la Ley CARES.

Al mismo tiempo, Puente se vio obligado a cerrar su cooperativa bilingüe de cuidado infantil. Los miembros del personal encontraron una manera de cambiar su programa de primera infancia a un modelo de apoyo en el hogar que continúa ayudando a los niños a prosperar. Y Puente convirtió su Programa de Liderazgo y Empleo Juvenil de verano en un programa de acceso remoto con talleres, desarrollo de habilidades, tutoría y oportunidades de empleo remunerado.

Puente también se vio inundado de solicitudes de ayuda para completar el papeleo de desempleo. El personal manejó 40 solicitudes solo en la primera semana, y pronto comenzó a hacer citas tres semanas después.

“Estaba agradecido de que Puente tuviera tanta infraestructura lista para moverse y adaptarse de una manera realmente rápida”, dice Mancera.

En el apogeo de la demanda, un promedio de 200 familias e individuos se presentaron cada semana para recibir alimentos de Puente.

“Fue extraño y sorprendente ver las líneas de automóviles que recorrían todo el camino hacia Harley Farms”, recuerda Mancera. “Definitivamente hubo muchas personas que se encontraron en una línea de alimentos por primera vez. La gente decía: “No puedo creer que estoy aquí … y les estoy muy agradecido por hacer esto”.

La comunidad se intensifica a lo grande

Joaquín Vargas es uno de los voluntarios de distribución de alimentos más firmes de Puente. El hombre de 37 años vive solo en Pescadero. Comenzó a aparecer por turnos: es un turno largo, desde las 12 p.m. hasta las 6 p.m. — en marzo.

Vargas dice que ha disfrutado el trabajo de descargar la comida de bolsas y cajas, dividiendo y reempacando todo lo que se carga en los autos de las personas desde cuatro estaciones de comida diferentes. “Pero más que nada, disfruto ayudar y ver a otros miembros de la comunidad ayudar también. Me gusta ver a la gente irse felizmente con sus bolsas de comida “.

Vargas también disfruta de la camaradería. Trabajar con Puente es una de las pocas veces que se conecta con los vecinos en estos días.

“Ayudar está en mi sangre”, dice. “Desde mi infancia, siempre había suficiente comida, la simple necesidad, no extra, siempre teníamos que buscar trabajos si queríamos comprarnos otras cosas o ayudar con más comida. Iba a ayudar a familiares, o trabajaba para ellos, y me daban un poco de dinero o comida para llevar a casa”.

Vargas ha disfrutado la comida que recibe a través de Puente, especialmente el brócoli, los tomates y las lechugas. Pero la mejor parte ha sido escuchar a otras personas reaccionar a la comida, y cuando le agradecen su ayuda.

“Es gratificante. No tengo los medios financieros para donar, así que puedo ayudar como voluntario “, agrega.

California no fue el único estado de EE. UU. Que experimentó escasez de alimentos en la primera ola de la pandemia. En todo caso, los estantes vacíos expuestos muestran cuán vulnerable era todo el sistema alimentario. Mientras la gente de la costa sur luchaba por encontrar leche y huevos, los granjeros de todo el país estaban tirando decenas de miles de galones de leche y rompiendo huevos porque sus mercados normales, restaurantes, hoteles y escuelas, se cerraron repentinamente.

Mientras tanto, comunidades como Pescadero, que depende en gran medida de los empleadores agrícolas, no pudieron encontrar fácilmente alimentos asequibles para alimentar a sus familias.

Ingrese a Pie Ranch, que encontró una solución que beneficia directamente a los agricultores y las familias con dificultades en toda la península. Se asoció con Fresh Approach, una organización con sede en Concord que lleva alimentos a las comunidades que lo necesitan.

En ese momento, Pie Ranch tenía un exceso de productos destinados a programas que ya no podían recibirlos. Entonces, cuando comenzaron a transmitir alimentos a Fresh Approach, los líderes agrícolas tuvieron otra idea: ¿qué pasaría si también pudieran agregar alimentos excedentes de otros productores de la región?

“La necesidad era evidente cuando llegó la pandemia. Las granjas estaban viendo un desafío para encontrar compradores para sus alimentos una vez que los restaurantes cerraron. Y la gente tenía problemas para encontrar y pagar la comida, y pagar sus facturas al mismo tiempo ”, dice Mona Urbina, gerente de programas culinarios en Pie Ranch.

Muy rápidamente, la granja creó un sistema de distribución completamente nuevo que mantiene las granjas solventes y lleva alimentos a 800 niños y adultos por semana, incluso a través de Puente. Está financiado por el Departamento de Agricultura de EE. UU. Y varias fundaciones.

Antes de la pandemia, Urbina era maestra de jardinería en la primaria Pescadero. Dirigió clases de cocina después de la escuela a través del programa Food Lab y trabajó con estudiantes de secundaria y preparatoria, ayudándoles a preparar el desayuno para sus compañeros. Supervisó la programación juvenil en Pie Ranch.

Ahora ella ayuda a dirigir el programa de ayuda alimentaria de la granja. Ella maneja el paquete, coordina a los voluntarios y se asegura de que todo cumpla con las reglas COVID-19 relativas al distanciamiento social y la seguridad alimentaria.

“Ser parte de esta solución significa mucho para mí, una que espero pueda ser un modelo para que otras granjas se conviertan en un agregado para distribuir alimentos a sus comunidades”, dice ella. “Es solo una pequeña solución sobre cómo podemos adaptarnos a estas situaciones, como la pandemia en la que nos encontramos”.

Yendo más allá

Durante la última década, TomKat Ranch en Pescadero ha donado 100 libras de carne de res por mes al programa de almuerzo en el Distrito Escolar Unificado La Honda-Pescadero, suficiente para suministrar dos comidas cada mes en todo el distrito. Cuando se cerraron las clases y Puente abrió su distribución de alimentos, Kathy Webster vio una manera de ayudar a muchas de las mismas familias y la comunidad en general.

“Cuando llegó la crisis, parecía que lo primero que salía de los estantes de las tiendas de comestibles era la carne. Entraste y estaba completamente vacío. Por lo tanto, el acceso a las proteínas, como la carne, se volvió más desafiante, especialmente en las áreas de alimentos subcontratados “, dice Webster, quien es el Gerente de Defensa de Alimentos de TomKat Ranch.

Para agregar a ese desafío, muchas grandes casas empacadoras de carne se vieron obligadas a cerrar debido a la exposición desenfrenada del coronavirus. El resultado fue un cuello de botella que aumentó el costo de la carne de res en casi todas partes. Incluso Taqueria de Amigos en Pescadero tuvo que publicar un letrero explicando a los clientes por qué el costo de algunos platos a base de carne, como la carne asada, fue repentinamente más alto.

“Aquí en la ciudad, ya hemos estado limitados por el hecho de que la Tienda de Pescadero se quemó hace tres años … por lo que el acceso local a alimentos frescos y fuentes de proteínas ya es extremadamente limitado”, señala Webster.

Para cuando la distribución de alimentos de Puente estaba en su apogeo, TomKat estaba donando hasta 200 libras de carne de res alimentada con pasto por semana, incluyendo carne molida, huesos y cortes de alta gama. Según Webster, esto ha ascendido a más de 2,500 libras de carne hasta ahora. TomKat también donó 4,800 libras de carne al Banco de Alimentos del Condado de Alameda en julio y agosto, lo que equivaldrá a unas 4,000 comidas en total.

“Solo cosechamos en cierta época del año. Pero todavía teníamos algo en el congelador, además de donación de carne destinada a las escuelas ”, explica. “Cambiamos nuestro plan estratégico para el año. Estamos dedicando una cierta cantidad de animales para que podamos continuar donando a Puente todas las semanas durante el resto del año. Estamos súper emocionados por eso ”.

La generosidad de TomKat ha inspirado mucho aprecio por parte de los locales, dice Rodríguez. “Sé que en las semanas que recibimos mucha carne molida de TomKat, los miembros de la comunidad decían:” ¡Hice hamburguesas! ¡Hice espagueti! “Fue realmente agradable escuchar que la gente estaba emocionada de llevarlo a casa y hacer lo que quisieran con él”.

TomKat ayudó a resolver otro gran problema local: la escasez de huevos. A un miembro del equipo, Annie Fresquez, se le ocurrió la idea de un programa piloto para ofrecer a las familias locales la oportunidad de tener gallineros cerca de sus hogares y compartir los huevos resultantes con los vecinos. Puente manejó el alcance. Quince familias acordaron participar, y TomKat construyó las cooperativas personalizadas este verano. Los destinatarios hicieron la asamblea final.

Dede Boies en Root Down Farm acordó criar a los polluelos, que fueron entregados en julio. El programa ha sido tan popular que “tuvimos personas llamando y preguntando si podían entrar en una lista de espera”. Desafortunadamente, no tenemos más cooperativas “, dice Rodríguez.

Sostenible en tiempos inciertos

La costa sur ha estado modelando la verdadera ayuda mutua en su mejor momento rural. En medio de una crisis que afecta la salud de las personas, la resiliencia económica, la educación y el acceso a los alimentos, la comunidad ha creado una serie de resultados notables.

Pero eso no es todo. En lugar de simplemente responder con medidas de curita, voluntarios y miembros de la comunidad, granjas y organizaciones sin fines de lucro se han unido para desarrollar soluciones estructurales completas que, una vez erigidas, continuarán sirviendo a los residentes a través de futuras crisis, sean cuales sean.

La pandemia de coronavirus ha hecho visibles las redes invisibles. No solo las formas en que la prestación de atención médica y los sistemas alimentarios son profundamente vulnerables, sino también las formas en que obtenemos nuestros alimentos. Las granjas y ranchos que proporcionan la comida. Las manos que lo recogen, lo empacan y lo desempaquetan. Ese conocimiento representa una nueva posibilidad de resiliencia a nivel local.

“Encontramos una nueva forma de colaborar con las granjas locales. Es poderoso para los lugareños saber que, a diferencia de las personas que tienen que recorrer millas para obtener sus alimentos, pueden obtenerlos frescos, a pocas millas de sus hogares “, dice Mancera. “También ha sido una buena oportunidad para nuestras granjas, particularmente las granjas orgánicas. Comenzaron a venderse muy rápido, fue como si la gente finalmente los notara de una manera más grande que antes “.

Eso incluye a algunos residentes de bajos ingresos, que ahora saben acerca de las cajas CSA (Agricultura apoyada por la comunidad, esencialmente una suscripción a una granja local).

Por ahora, la demanda de alimentos ha disminuido lo suficiente como para que Puente cambie a una asociación de distribución de alimentos más limitada con Pie Ranch (para frutas y verduras) y TomKat Ranch (para carne), cupones para el hipermercado Pescadero Growns Farmer’s Market y tarjetas de regalo . El programa de asistencia financiera de Puente ha vuelto a un nivel de servicio habitual, en comparación con la demanda frenética de esta primavera.

Los esfuerzos de Puente han sido posibles gracias a las donaciones de emergencia de los socios de la fundación, un donante importante y los muchos partidarios que continúan donando al Fondo de Ayuda COVID-19 de Puente.